Sunday, April 30, 2006

the following three paragraphs are adapted and excerpted from a larger article by R. Eliezer Weger, a Modzitz Chassid from Rechovot, and a dear friend. You can read the entire piece on the Modzitz website.

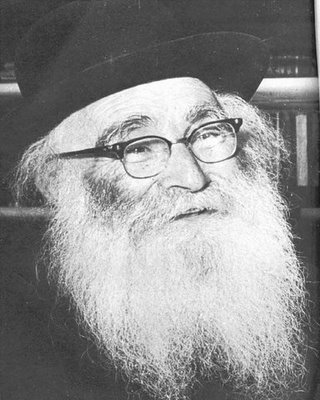

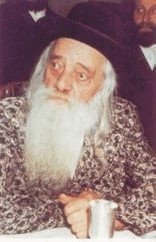

This Monday night and Tuesday - the 4th of Iyar - is the 22nd yahrzeit of the previous Modzitzer Rebbe, Rebbe Shmuel Eliyahu Taub (known as the Imrei Aish), zecher tzaddik v'kadosh l’vracha. For anyone who was zoche to meet, hear, or see the Imrei Aish, he left an indelible impression on their memories, a living link to the beauty and depth of Polish Chassidic Jewry from before the war, and the noble and challenging efforts to rebuild Torah Chassidic Jewish life in Eretz Yisrael in the 1930s through the 1980s.

The task of rebuilding the Chassidus in Eretz Yisrael was no simple one, especially since he had left his father, Rebbe Shaul Yedidya Elazar zt"l, and settled with his family in the newly developing city of Tel Aviv, after he and his father, the Rebbe, had visited here [in 1935]. But the distance and non-conducive environment didn't dissuade him, and Modzitz developed a new, vibrant focus in the cradle of the new Jewish State. He became a member of Tel Aviv Rabbanut [Rabbinate], after nearly being forced to return to Poland. Carefully balancing the emotional overflows from the Holocaust and the new State, with the deeply rooted values of Agudist-Polish Chassidic Jewry, the Imrei Aish earned the love and respect of all kinds of Jews, from all walks of life. The Modzitzers who survived or fled Europe flocked to him, as did hundreds of others who found his home and guidance an Ir Miklat (City of Refuge) from which to rebuild their own lives. To this very day, one sees on any given Shabbos by the Rebbe Shlita’s Beis Medrash heads covered with hats, spodiks, kippot srugot, streimlach, and even some hastily donned kippot, all by people who definitely consider themselves Chassidei Modzitz... talmidim of Rebbe Shmuel Eliyahu zt"l.

Regarding his niggunim: there is no question that they were hewn from the same sources as David HaMelech's Tehillim, of Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi's writings, the lifeblood of all that seeks to return all that we can to the glory of our Creator. The very walls of the Tel Aviv Beis Medrash danced with the Kaddish on Rosh Hashana; rivers of emotion flowed with each waltz; and hearts yearned for the Geula Sheleima with each Tish niggun. Although his father Rebbe Shaul Yedidya Elazar zt"l is universally recognized as the Chassidishe composer par excellence, the Imrei Aish was nearly his equal in some ways, and some feel he even exceeded in his waltzes. Just hearing the niggun he composed in 1967 when he first was able to return to the Kosel gives you a clear insight into what kind of Kedusha [holiness] inspired him, lifted him and countless others at the time... and to this very day. [Many of his niggunim, such as "Lo Savoshi" and "Kadsheinu B'Mitzvosecha" have become "velt niggunim," sung throughout the Jewish world.]

We have also previously discussed the Imrei Aish’s “Chamols”, but it is worth repeating here: "Chamol al Ma’asecha." The words are recited just after Kedusha in several of the Yamim Noraim prayers - both on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. "Have compassion on Your creatures, and rejoice in them. And those that trust in You should say, in justifying those whom You carry [the Jewish people]: May the L-rd be sanctified upon all of His Creation, for You have sanctified your holy ones with Your sanctity; it is indeed fitting for the Holy One to be praised by his holy ones." Year after year, the Imrei Aish of Modzitz would compose a new niggun to these words. And year after year, the Modzitzer Chassidim would be uplifted -- for an entire year -- with the new "Chamol." It is almost impossible to put into words what this is. Suffice it to say that these are some of the most lofty, soulful and uplifting niggunim one can ever hear. Anyone who's heard them knows I'm not exaggerating. Only one that I know of has been released on an official recording - the one from 5715 or 1954. Besides Modzitzers, they have also inspired the likes of Reb Shlomo Carlebach -- whose "Ani Ma'amin" and "Lecha Ezbach" tunes both bear the influence of the Imrei Aish's Chamols. Recently, Modzitz opened a Musical Heritage Institute, for the preservation and documentation of niggunim. One of their first projects was to release a series of recordings of the Imrei Aish's niggunim. To date, recordings of the "new" niggunim for the years 5723-5732 [1962-71] have been released. So, by obtaining these recordings from the Institute, you can get to hear another 10 Chamols!!! Well worth it!

***********

Recently, Modzitz’s publishing arm, “Machon Aish Tamid,” published the sefer Imrei Aish, with the Rebbe zt”l’s chiddushim [innovative insights] on Torah, Moadim [holidays], and Likkutim [miscellaneous topics]. What follows is a small part of what he says about Negina.

Negina in Modzitz, says the Rebbe, has a place in Avodas Hashem that is not found in other paths. To explain, it is generally held that the way to dveykus [attaching oneself, clinging] to Hashem is only through Machshava, the realm of Thought. However, this method has a disadvantage, in that it is not open to sharing with others, which can be done through speech. However, in speaking one can share his ideas with and arouse others, but because of his efforts in communicating to the other[s] – the listener[s] – one cannot focus on dveykus to Hashem.

However, there is another way – through sound [Kol], specifically the musical sound of a wordless niggun. This combines both advantages [of thought and speech], without any lacks. That is, it has the advantage of Thought, which can be deepened and lead to dveykus baShem. But not only does it lead to dveykus, Negina can also lead one to Teshuva [return to Hashem; penitence]. Moreover, it has the advantage that speech has, in that it can involve others. That is, those who are in earshot of the niggun can hear it, join in, and deepen their experience by attaining dveykus in Hashem and arousal to Teshuva. Thus the niggun has the advantages of both Thought and Speech, without the disadvantages.

The Rebbe specifies that when he refers to niggun, he is referring to song without words, for only in this way can a deeper experience be attained. Even though at times one may sing the tune with words, the deepening is in the tune and not the words. This is because the words are recited several times throughout the day in various forms, and therefore his main effort is in the tune. [It should be noted as well, that in Modzitz, only the one that leads the tune generally sings it with the words, while the Rebbe and the Chassidim that sing along with him only sing the tune.]

Rebbe Shaul said that a niggun composed from the knowledge of musical theory and notation is not a true niggun, for it does not come from the heart. Only a niggun that is formed in the heart and thought can enter another, as “dvarim hayotzim min haLev, nichnasim el haLev – matters which come from the heart, enter the heart” [of another]. Such a niggun can become deeper and deeper, and pave the way to dveykus in Hashem and arousal to Teshuva.

Finally, as we approach Israel’s Memorial Day for its soldiers and its Independence Day, it is proper to relate what today’s Rebbe Shlita [he should be well] wrote: “I recall that during the Six-Day War, there were young men who were called up to go to the War in the middle of the night. When they returned, they told me that they took a tally, and whoever went into the Rebbe [his father, the Imrei Aish] for a blessing before departing for the War, returned unharmed. Hashem should bless us, that just as he [the Rebbe Zt”l] protected us in his lifetime, he should do so now.”

Zechuso Yagein Aleinu, v’al Kol Yisrael, Amen!

Wednesday, April 26, 2006

THE MODZITZER REBBE

We are very pleased to announce that the Rebbe Shlita has returned home from the hospital, just before Pesach, for home-based rehabilitation. His health is improving steadily, progressing to the point that he wrote a letter (in his own handwriting), which was posted in the main Beis Medrash in Bnei Brak, wishing a Chag Kasher V'Sameach to all of the Chassidim and friends of Beis Modzitz. There is still a long way to go on the road to recovery, but Baruch Hashem, major steps have been taken down that road. We ask that you continue to daven for the refua shleima [complete and speedy recovery] of

Rebbe Yisrael Dan ben Rivka Zlata

רבי ישראל דן בן רבקה זלאטע

UPCOMING YAHRZEIT OF THE IMREI AISH ZTUK”L

The 22nd yahrzeit of Rebbe Shmuel Eliyahu of Modzitz Ztuk”l, the previous Rebbe, is this Monday night and Tuesday, the 4th of Iyar. The Imrei Aish [the name of his sefer, recently published] was zoche [merited] to compose some of the most beautiful niggunim there are.

This Shabbos, which is also Rosh Chodesh Iyar, will feature a special gathering of the Chassidim in the Rebbe Shlita’s Beis Medrash at 20 Habakuk Street in Bnei Brak in preparation for the yahrzeit.

The Yahrzeit Seuda itself is Monday night, with Ma’ariv at 8:15 pm, followed immediately by the Seuda. In addition, there will be an Aliya L’Kever [visit to the gravesite] on Tuesday, with transport leaving from the Rebbe Shlita’s Beis Medrash at 2 pm, estimated to arrive at Har HaZeisim [Mount of Olives] in Yerushalayim at 3 pm.

Watch this blog for more on the Imrei Aish - shortly.

THE MODZITZER’S ROAR

I recently contributed this story to our good friend, Reb Lazer Brody’s “Lazer Beams.”

CONVERSATION ON NIGGUNIM

I was also a significant contributor to this post by another good friend, A Simple Jew. It was posted yesterday [Tuesday].

RABBI WEIN ON JEWISH MUSIC

Although this is not brand new, I recently discovered this very interesting perspective, from Rabbi Berel Wein, the famous historian and one of the leading independent thinkers of our time.

REB SHLOMO CARLEBACH TELLS OFF MBD

Interesting video confession by MBD, thanks to my friend Chaim of the Life-of-Rubin blog.

DIVREI CHAIM UPDATE!

This week's English HaModia weekly has some wonderful stories about the Divrei Chaim, including one about a bracha he once gave to Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, Rav of Yerushalayim.

Friday, April 21, 2006

This Motzaei Shabbos and Sunday, the 25th of Nisan, is the 130th yahrzeit of Rebbe Chaim Halberstam of Sanz (1793-1876), known as the Divrei Chaim after his magnum opus on Halacha. The Divrei Chaim was born in 1793, in Tarnograd, Poland. He was a talmid of Rebbe Naftali Zvi Horowitz of Ropshitz.

He went on to move to the town of Sanz where he founded a Chassidic dynasty. He attracted many followers due to his great piety. The Sanz dynasty today is represented by the Sanz-Klausenberg and the Bobov dynasties.

The Divrei Chaim was acclaimed by the leading rabbis as one of the foremost Talmudists, Halachic and Kabbalistic authorities of his time, he received queries from communities all over the world. His responsa, as well as his Torah commentaries, published under the title Divrei Chaim, reflect his Torah greatness, his humility, and his compassionate nature. He was a champion of the poor and established many organizations to relieve them of their poverty. His compassion and generosity was legendary; he literally gave away everything he had for the needy; and went to sleep penniless.

During his 46 years as Rabbi of Sanz, that city was transformed into a vibrant center of Chassidus, attracting tens of thousands of followers. Among his disciples are counted such leaders as Rebbe Shlomo HaKohen of Radomsk, Rebbe Meir Horowitz of Dzikov, and the Yetev Lev of Sighet.

Rabbi Chaim's five sons all became famous tzaddikim, the most prominent of whom was Rebbe Yechezkel of Shiniva. One of his daughters married Rebbe Mordechai Dov, the first Rebbe of Hornesteipel. The Divrei Chaim passed away in Sanz, Poland in 1876 (25 Nisan 5636 on the Hebrew calendar).

One of my favorite stories of the Divrei Chaim is found in the sefer “The Zeide Reb Motele” by Rav Avraham J. Twerski.

When still very young, the outstanding Torah scholar, R. Baruch Frankel, known for his Talmudic commentaries and Halachic responsa, Baruch Taam, chose R. Chaim as a husband for his daughter, Rachel Feige. Shortly before the wedding, the young woman found out that R. Chaim had a severe limp, and she refused to go to the chupa. R. Chaim asked to have a few words with her in private, and she agreed to speak with him.

Although no one was privy to their conversation, the story circulates that R. Chaim asked his kallah [fiancee] to look into the mirror. When she did so, she saw herself with a severe deformity. He then told her that she had been destined to be deformed, but since she was his basherte (predestined mate), he had intervened, spared her of the pain and took her deformity upon himself. Needless to say, Rachel Feige consented to marry him.

R. Baruch used to say, “My son-in-law may have a weak leg, but he has a very strong mind.''

***

And this one, from the same book:

Rebbe Eliezer of Dzikov, who was a mechutan (his son's father-in-law) of the tzaddik of Sanz, was once very ill, and the tzaddik visited him. When he entered the sick-room, he found the family at the bedside. R. Eliezer was sighing deeply.

The tzaddik said, "Mechutan! What is all the sighing for? You know that it is no more than a transition as from one house to another, or taking off one garment and putting on another.''

R. Eliezer pointed to his family. ''But I must provide for them,'' he said.

The tzaddik of Sanz said, “No need to worry, mechutan. I will provide for them. I will be a father to them and care for them like for my own.”

''But, Sanzer Rav,'' R. Eliezer said, ''we are soon to have Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. I serve as chazan (one who leads the services), and you know that when I sing Ein kitzva lishnosecha ("There is no limit to Your years"), the heavenly angels join in song and clap along with me."

The tzaddik of Sanz became very contemplative. “In that case,” he said, “have someone warm the mikva.”

The tzaddik remained in the mikva for four hours. Upon emerging from the mikva, he appeared exhausted but in good spirits. He said, “We can keep him with us.”

R. Eliezer lived an additional thirteen years.

Sanzer niggunim are sung far and wide in Chassidic and Orthodox circles.

An album of niggunim called Ki Vo Moed, sung by Sanzer Chassidim has been released. It has ten tracks and features solos by Efraim Mendelson, Shlomo Luk, Naftali David and the child soloist Moshe Cohen.

Some of Reb Shlomo Carlebach’s stories about the Sanzer are here.

Reb Michel Twerski’s tapes, In the Footsteps of the Chassidic Masters,

Volume IV, (five tapes), covers the life and times of Rebbe Avraham Yehoshua Heshel, the Apter Rav; and Rebbe Chaim Halberstam, the Sanzer Rav.

UPDATE! This week's English HaModia weekly has some wonderful stories about the Divrei Chaim, including one about a bracha he once gave to Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, Rav of Yerushalayim.

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

The Bostoner Rebbe Shlita, Rebbe Levi Yitzchak Horowitz, making the Bracha

The Chassidim singing, including Rav Dovid Gottlieb and Reb Moshe Shimon Horowitz, the Bostoner Rebbe's grandson

The Rebbe continuing with the Tehillim recited together with the Bracha

Toward the end, the Chassidic Dance. Second from the left, HaRav Mayer Horowitz, the Rebbe's son. The Bostoner Rebbe Shlita is on the right.

Toward the end, the Chassidic Dance. Second from the left, HaRav Mayer Horowitz, the Rebbe's son. The Bostoner Rebbe Shlita is on the right.

Related post is here...

Monday, April 10, 2006

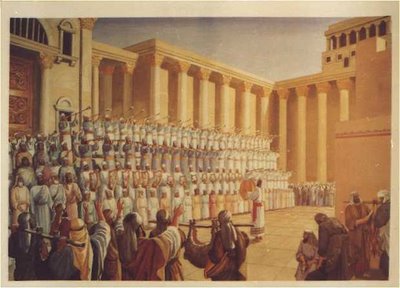

The Levitical Choir - click to enlarge

The Levitical Choir - click to enlarge

On the way to the Korban Pesach [sacrifice of the Paschal lamb]:

The priests allowed us to enter into the Courtyard, one group at a time. When one group was finished, another would enter. All the while, the Levites stood on their platform and sounded blasts from their shofars (rams' horns) and silver trumpets.

The Levitical choir also included singers and musicians who played on trumpets, harps, lyres, and cymbals. They sang the festive Hallel songs of thanksgiving. Everyone who had entered with their Passover offering, also joined in and sang along. When we finished the Hallel, we would start all over again!

Again, for me, we lead off with Modzitz. Modzitz has its own Pesach Niggunim page

Featured are: V'hi She'amda and Chad Gadya for the Seder; B'tzeis Yisrael, Odcha and Ana Hashem from Hallel; the classic Tefillas Tal, composed by the Imrei Shaul in 1936; V'koreiv P'zureinu from Musaf; and Baruch Elokeinu. There is another B’tzeis Yisrael on the main music page as well as the following: Hodu LaShem from Hallel; Kah Keili, a Yom Tov prayer recited before Musaf, and Bnei Veischa from Musaf. Of course, the Kaddishes from the main music page can also be used in the Yom Tov davening. I should mention, again, that the Modzitzer Rebbes all were and are prolific composers, and this is but a mere fraction of their output for Pesach. It was very common for the Rebbes to compose new niggunim every Pesach. Thus, there are many niggunim for B’tzeis Yisrael, which were composed almost every year; other favorites were V’Hi She’amda from the Seder, and Hodu LaShem from Hallel. R. Ben Zion Shenker, as well, has composed niggunim for these sections. Modzitz also has its own Haggada, Ashei Yisrael.

Reb Shlomo Carlebach has several Pesach niggunim. From the Haggada, Shomrim Hafkeid, v’Nomar L’fanav, and Adir Hu. Of course for Hallel, there’s a Carlebach niggun for just about every section. And from the tefillos, Bnei Veis’cha, v’Hashev Kohanim, and Melech Rachaman, all from Musaf.

A beautiful niggun for Bnei Veis’cha [a different one] is on this recording, “Nevertheless” by Aaron Razel & the Witt Children, the last track. One can find a lot of Reb Shlomo's teachings about Pesach on this page, and his Haggada here.

Chabad has a fine share of niggunim for the holiday. V’Hi She’amda,

Mimitzrayim Ge’altanu, Keili Ata v’Odecha from the Alter Rebbe, V’Karev Pzureinu, Echad mi Yodea [Who Knows One?] in Russian (see also below).

Niggunei Pesach, 11-1/2 minutes long, includes: V’Hi She’amda, Al Achas Kama v’Kama, Ata Bechartanu, and Mimitzrayim Ge’altanu

In addition, there are numerous wordless niggunim, including several for Shabbos and Yom Tov.

I just found some beautiful Bobover niggunim: B’tzeis Yisrael;

Brach Dodi, from Shir HaShirim; Hotzi’anu m’Avdus L’Cherus;

V’Hi She’amda; and Shira Chadasha.

And there are some nice videos of one of the Bobover Rebbes [there are now two Rebbes]:

Ne’ilas HaChag [festival closing] at the night following Pesach

Escorting the Rebbe home to his porch, from the same night.

Here you can find, yes, a Digital Haggada! To assist people with limited Hebrew skill and any unfamiliarity with classic Passover melodies, Judaism.com is offering the Digital Haggada: free downloads of MP3 files of essential excerpts from the Passover Haggada. These tracks were recorded by Chaim Davidson, a Pittsburgh Baal Tefilla (leader of synagogue services). Interestingly enough, the B’Tzeis Yisrael presented consists of two Modzitz niggunim, the first being Ben Zion Shenker’s tune; and the second, a niggun originally made for Kaddish by the Imrei Aish [previous Rebbe], often sung to Shir HaMaalos and Keil Adon. You can also download the entire Digital Haggada as a zip file.

Hat Tip: Jewish Music Web Center

The Jewish National and University Library – National Sound Archives’ presentation for Pesach consists of twelve different renditions of the famous song from the latter part of the Pesach Haggada, Echad mi Yodea [Who Knows One?]. These digital fragments, in MP3 format, illustrate the range of Jewish communities represented in the Archive’s more than 7,000 hours of recorded music: Chassidim - Chabad; Israel; Netherlands; Greece - Corfu; Italy; Persia; Greece – Salonika; Morocco – Meknes; Turkey; Hungary; Morocco – Tetuan; and Yemen.

The Chabad rendition is in Russian [Ech ty zemliak, zatshem zhe ty durak], arranger by Andre Hajdu and sung by Berel Zaltzman. It was recorded at a performance in Jerusalem in 1976.

I’m sure I’ve only hit the “tip of the iceberg” here. Readers are asked to send in their favorites in the comments...

Friday, April 07, 2006

Rabbi Aryeh Levine, ZT"L

Rabbi Aryeh Levine, ZT"LToday is also the Yahrzeit of Rabbi Aryeh Levine, who was known as both the "Tzaddik of Yerushalayim, and "A Tzaddik in Our Time." He is not known for Negina, but his life was certainly a Great Song to the One Above, as shown in the following anecdotes:

The Man Who Mistook His Wife's Foot for His Own -

Actually, he wasn't mistaken

The Talmud rules that "A man's wife is as his own body." Rabbi Aryeh Levine (d. 1969), known as "the Tzaddik of Jerusalem," exemplified this ideal. On one occasion, when accompanying his wife to a Jerusalem clinic, he explained to the physician: "Doctor, my wife's foot is hurting us."

***

The Winter Coat

The following anecdote I heard personally from R. Benjy Levine, a grandson of Reb Aryeh's. I don't recall if it was an actual event, or just a mashal [parable] that he told:

In the middle of a very cold winter, two men came before a Rav, disputing over a winter coat. It turns out they were father and son.

The father began: "I am a very old man, and the winter cold really gets to me, I must have this coat to keep me warm!

The son responded: "I need to go outside to work every day to support my father and me. Surely I deserve this coat."

The Rav thought it over, and declared: "I need some more time to decide your case. But before I do, I want you to both come back tomorrow, and make your best claim -- for your opponent."

A bit bewildered, the father and son went home, and came back the next day.

The father began, "My son works hard to support us. He needs this coat when he goes outside to earn a living."

The son responded, "Oh no! My father is elderly and cannot make it through the cold winter without a warm coat, even inside. Surely he deserves it.

The Rav then went over to a closet in his house, took out a winter coat, told them that it was an extra coat that he didn't need, and gave it to them.

Now they were really confused. "Tell me, Rabbi," they both said. "Yesterday, when we were here, didn't you have this extra coat?"

"Why, yes," the Rav replied.

"So why didn't you give it to us then?"

"Well, yesterday, when you came here, each of you said that you have a coat, and 'it's mine.' So I thought, 'I, too, have a coat and it's mine.'

But today, when each of you said, 'I have a coat, but I don't need it, it's his,' so I thought, 'I, too, have a coat, and I don't need it, so it's yours!' "

Today is the 9th of Nisan, yahrzeit of Rebbe Chaim Meir Hager, the "Imrei Chaim" of Vizhnitz [5641/1881-5732/1972]. Vizhnitz is a Chassidic dynasty that is deeply rooted in Negina. The article below, by Lewis Brenner,

Today is the 9th of Nisan, yahrzeit of Rebbe Chaim Meir Hager, the "Imrei Chaim" of Vizhnitz [5641/1881-5732/1972]. Vizhnitz is a Chassidic dynasty that is deeply rooted in Negina. The article below, by Lewis Brenner,originally appeared in The Jewish Observer, is also available in book form in the ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications Judaiscope Series. It conveys the majesty of the Negina at his Tish, and speaks for itself.

***

Rabbi Chaim Meir Hager, who had been revered as Vizhnitzer Rebbe for 35 years, passed away in Eretz Yisrael on the Thursday night before Pesach, 5732. On the following day, an estimated 50,000 mourners accompanied his aron to its final resting place.

He had a huge following, including the thousands of settlers of Shikun Vizhnitz, and the hundreds of students of the Vizhnitzer Yeshiva, both in Bnei Brak; he was a member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah (Council of Torah Sages) of the Agudath Israel of Eretz Yisrael; he was the scion of a noble Chassidic dynasty; but, perhaps equal to all of these elements, his personal warmth, the majesty of his Tish, and the triumph of joy over adversity that he personified, won him vast admiration beyond the confines of any one group.

The shtibel on Ross Street in Williamsburg was packed. People were literally hanging on to the walls. I was perched on the oversized cast-iron radiator in the corner, one hand mopping my brow with my handkerchief, the other hand holding on for dear life to the gartel of my partner on the radiator. We didn't know if the radiator was warming us or if the heat was generated from the assembled multitude. This was a multifaceted group of Chassidim from Galicia, Bukovina, Rumania, Hungary, Marmorosh, Transylvania - indeed from all over the globe, bent on one purpose: spending the Shabbos with the Vizhnitzer Rebbe, who had just arrived from Eretz Yisrael to seek support for his beloved project, the building of Shikun Vizhnitz in Bnei Brak. His avowed purpose was the rejuvenation of Chassidus after the Holocaust, which left many in despair; reciting Kaddish over Yiddishkeit, frumkeit and especially Chassidus. In our minds, we were mulling over the Rebbe's words regarding the Baal Shem Tov's promise to his great disciple and shliach tzibbur, Reb Yaakov Koppel Chassid, from whom the Rebbe was a seventh generation descendant – "Your issue will lead Klal Yisrael to welcome Moshiach."

Suddenly all was quiet. The Rebbe silently made his way through a hastily formed lane, the throng held back by broad shouldered Chassidim. He took his place at the head of the table and, with outstretched arms welcoming the Shabbos, he began, "Gut Shabbos, Gut Shabbos, Gut Shabbos, heiliger Shabbos, taiyere Shabbos, shreit shet, Yiddalech, Gut Shabbos."

Thus, at about eight o'clock, began the Tish which was to last into the early hours of the morning. Shabbos knows no night, the Rebbe would say, quoting Rashi in Masechta Shabbos - Friday is considered the night of Shabbos. Shabbos is completely day, made up entirely of light, life and purity. He recited the Shalom Aleichem in the nusach made famous by three great Vizhnitzer Rebbes before him, intoning each phrase distinctly and in his own unique manner. Shabbos shulem u'mevoroch - Shulem aleichem, malachei hashareis, malachei hashulem, malachei elyon!

He sang with a clear and resonant voice, broken from time to time by a sob - a tear shed out of the joy with which he greeted the Shabbos - and by a deep krechtz [sigh, groan] emanating from the soul which longed with such great anticipation for Shabbos HaMalka, the Sabbath Queen.

He went through the recitation of "Shalom Aleichem" and the entire "Ribon HaOlamim" without singing, merely chanting the words. Upon its completion he picked up the hadassim [myrtle leaves] filled with spices and recited the "Borei minei b’samim" [blessing over spices]. Thus, with an addition to his great soul and the scent of m'danei asa [myrtle], he began to say "Eishes Chayil" in a half-singing, half-chanting tone - a tradition brought down from the holy Zeides of Kossov, who labored and toiled in the cradle of Chassidus, in the mountain valleys where Russia, Poland, Rumania, and Hungary touched each other. The u-bu-bu-boy and the lingering sounds of the Vizhnitzer nusach, elongating many words and dragging the syllables of others, were the trademark of the dynasty founded by Reb Yaakov Koppel Chassid, established in the Galician village by his son Reb Mendel and fortified by his grandson Reb Chaim. The next generation had its own Reb Mendel, known as the Tzemach, from whom sprouted the present dynasty. As the son-in-law of the great Rizhiner, he set up his court in Vizhnitz, a hamlet in Bukovina, not far from the palace of the Rizhiner in Sadigura.

The Rebbe continued to recite the "Askinu Seudasa," with the unmistakable nusach, revealing in each phrase his thoughts and emotions. One could feel the expression of "simcha b'lev nishbar" - rejoicing with a broken heart - a melody peering out of the cracks of a heart, overflowing with the joy of the advent of Shabbos. His progenitors dwelled upon the mysteries of the Shabbos, the holiness of the Shabbos in all of their writings. He, the Rebbe, was attempting to convey the joy of the Shabbos. To all who entered his sphere of influence he opened a door to the enjoyment of the Shabbos; to sense its happiness and to open one's heart and soul to its flood of purity and sanctity, contentment and ecstasy.

The shtibel [Chassidic house-shul] was filled with all kinds of Jews, all types of Chassidim, attracted to the Rebbe's voice and look, as to a magnet. He led, he directed, he guided with a wink, a gesture, a movement. The entire group swayed as he swayed; sang, as he sang; cried, as he cried; smiled, as he smiled; everyone, as if transposed from this world to another, elated, uplifted, and overjoyed. This was his magical power of "taking the olam," the entire group, molding them into one unit, ready to do the Will of the One Above.

He proceeded to make Kiddush. As he uttered the words "Yom HaShishi," we all strained to get a glimpse of his face. With the entrance of the Shabbos his entire appearance changed. It was as if he had grown a foot taller. His bearing, so regal all week long, was even more pronounced on Shabbos. He was immaculate in dress. Every hair of his beard was in a pre-ordained place. His peyos were neatly curled and smoothly blended into his beard. His face was radiant with joy. Yet he was "poshet tzura v'lovesh tzura" - his facial expressions changed with the mood of the words he chanted. He intoned the words of the Kiddush, some hurriedly and others he lingered upon; stressing, explaining, emoting - all part of the same process of involving all around him in the happiness he felt in the Shabbos. Here before our eyes was the Rebbe who personified the humility of Kossov, the majesty of Rizhin, the wisdom of Ropshitz, the piety of Chernobyl and the kindness of Apt. In his veins flowed their blood and in his conduct he eternalized their message. His path was a synthesis of all of these great dynasties and he sought to recreate their former greatness in his renaissance of Chassidus after the great Holocaust.

No sooner had he finished the Kiddush, partaken of the wine, when he immediately lifted his hands to conduct the entire olam in a new song - a melody he had composed on his way to America. He enjoyed a new niggun and lent his ear to every type of song. He once told us that his entire body is one niggun; from the tips of his toes to the top of his head he echoed with song.

The entire shtibel trembled as the sound reverberated, as all were pervaded with his joyful presence. He was in full command at all times. He glanced around the room and scrutinized us all - nothing escaped him. He recognized faces he hadn't seen in forty years and he embraced relatives he hadn't seen since before the war. He drew everyone close with his sharp and friendly look.

Thus, the Tish continued and the first course was served. He nibbled at the fish and distributed the shirayim [the “leftovers” from the Rebbe’s portion] - being meticulously careful to hand out the fish on a special fork to those he knew as uninitiated in the habits of the Chassidim. He would avoid violating anyone's feelings and strove to make everyone feel at home.

After the distribution of shirayim to the dignitaries, the platter was pounced upon by the Chassidim who were even satisfied to have only touched the platter. Others, who were luckier, diligently divided up their spoils with their neighbors and to all newcomers - especially to those who were not Chassidim. Remember, this was Vizhnitz where all were drawn close to the Rebbe by the Chassidim who were taught to attract all - even the most distant. Their motto was summed up in the words of the Rosh Hashana prayer of V'yishme'u rechokim v'yavo'u, "Those distant will hear of you and come close to you."

All is silent. The Rebbe begins to chant the "Kol Mekadesh" with the tune of his forefathers, repeating some words and stretching out others. He repeats the word "meichalelo" three times. The last time he pronounces it as "mochal-lo," hinting at a Chazal [saying of the Talmudic Sages] that states - "If a man keeps the Shabbos, even if he was guilty of idolatry, his sins are forgiven."

The Chassidim press forward, eager to see the Rebbe, and to swallow each word he recites. At times, the Rebbe pauses to wipe a tear from his eyes, but he is not crying. He is enjoying the Shabbos and expressing his happiness. His voice rings loud and clear, and it tears into every heart. It is difficult to forget his imposing presence, his resonant voice and his loving smile.

The "Kol Mekadesh" is followed by a lively niggun, a dance melody, and the Rebbe is careful to make sure that all are responsive to his urging to participate. Soon the entire room is reverberating - everyone is awake, swaying back and forth to the rhythm.

Following the soup the Rebbe pauses and then begins the "Menucha V’Simcha." This is no ordinary tune. It is a symphony. Its composer was the great Reb Nissan who had sung in the court of the Rebbe's father (known as the "Ahavas Yisrael" after his sefer), Rebbe Yisrael, of blessed memory. The Rebbe sang the first movement. It was repeated by the entire group. He then carefully taught the group the refrain and was gratified by the quick response and some able voices. His pleasure was obvious, for his face shone. But pity the one who went off key! No matter how many people were assembled, his sensitive ear would rebel at a false note and he would pound on the table with his fingers, interrupt the singing, and have the olam repeat the melody perfectly.

"Menucha V’Simcha" sometimes took close to twenty minutes by the clock! But who was looking at the clock? We had lost all sense of time, as if transposed into a Gan Eden - some Olam Haba beyond space and beyond time. Our joy knew no bounds as we sang and opened our ears to the voice of his singing, for he pierced many ears that were tone-deaf and many hearts that were laden with grief and adversity. He taught us how to daven, how to chant, how to sing, and we felt closer to him with every note. He blended everyone into one symphony of prayer and song. From hundreds of individuals, drawn from dissimilar backgrounds and temperaments, he welded together one solid group of Chassidim bent on one purpose - tasting the joys of the Shabbos.

While eating the main course the Rebbe was humming to himself and mulling over in his own mind the thoughts he was going to say in his dvar Torah. Even though he was so engrossed in his own thoughts, he was alert to the entrance of any visiting dignitary - Rebbe or Rav or Rosh Yeshiva. He had each seated according to his station and was reverent and respectful to all, sidestepping his own dignity to honor all. His frequent question asked of his guests was, "Where does one find simcha? Can joy be purchased in a special store?" I once gathered enough courage to answer him that happiness was to be found by the Rebbe. His face lit up, and smiling from ear to ear, he bestowed his usual blessing: "A zis leben oif dir, mein kind [a sweet life to you, my child]."

His dvar Torah was always preceded by a serious niggun sung in undertones, and erratically interrupted by the Torah itself. His Torah words were filled with mystical combinations and numerical equivalents [gematrias], laboriously put together. He always stressed the theme of Shabbos: enjoying the Shabbos, hallowing the Shabbos. He would always inject some mussar, criticizing those who slept away most of the Shabbos. He implored all to taste the Shabbos and to sense its beauty, holiness, and joy. No heart was left untouched and no mind was left unchallenged. He had something to say to everybody - to the great scholar and the simple Chassid alike. He appealed to all, embraced all, and inspired all.

The bentchen [grace after meals] was followed by a joyous dance, with the Rebbe stationed in the center, observing all who danced. Here he recognized a face he hadn't seen in ages and there he patted a Chassid on the back, thanking him for some long-forgotten favor. People who had in some way been of service were astounded to hear him offer his thanks and blessings to them after decades of separation. He never forgot a face, a name, a good deed. As the dancing proceeded, he immersed himself into it, constantly urging the olam from his station to increase the intensity of the singing and dancing. The olam responded with more ecstasy and greater enthusiasm.

After a while the table was reset with fruit and kugel, and the Rebbe sat down for what was known as the Second Tish. The older Chassidim went home, and the younger people, with greater resources of energy, remained. It was well past midnight. After distributing the fruit and kugel, the Rebbe would retell oft-told stories of his great ancestors and of other great Chassidic leaders. Special songs were sung upon various occasions. Most often he had one of the Hungarian Chassidim sing the song of the Kaliver [Rebbe] that dealt with the coming of Moshiach ("Shirnok Rinok"). After each stanza he would sing the Hebrew words as tears rolled down his cheeks. He always followed this niggun with a very joyful dance-song, which sounded like a triumphant welcome to the expected Moshiach.

At this second Tish the Rebbe began to call over the bachurim, requesting that each say a dvar Torah. After each bachur divested himself of his dvar Torah, the Rebbe would add to it, correct it, and make sure that the source be given due credit. He would literally trade dvar Torah for dvar Torah, and embellished each one with stories from the lives of the authors. At this Tish he would usually sing "Kah Ribbon Olam." The niggun, the gestures, and the trembling voice alerted all to the holiness of Ma'amad Har Sinai [the receiving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai] and all rose to their feet to honor this momentous occasion.

Following the Second Tish, the Chassidim danced to either a wordless niggun, or to the famous "HaShir V'HaShevach," or to the Vizhnitzer "Shevach Ykar Ugdula." Once experienced, it was difficult to forget the sight of the Rebbe in the early hours of the morning as alert and enthusiastic as a youngster, urging all of us on to greater heights of joy and ecstasy.

The Rebbe sat down to a third Tish where the bachurim were the center of attraction. There each had to say his dvar Torah and listen to the Rebbe's comments. At this Tish he distributed korsh (a cake made of yellow corn meal), served with herring and schnapps [whiskey]. By this time all sleep had been forgotten and the remaining olam was as alert and as eager to enjoy the Shabbos as the Rebbe. But it was getting late and at about 2 a.m. the Rebbe would begin to ascend the steps to his apartment above. He turned around to us, and seeing that we longed for more he began to sing the "Odeh LaKeil." The building echoed with our singing of the refrain, and as he mounted the steps, the Rebbe turned around and sang another stanza. The song spoke of rejuvenation and of constant devotion - themes the Rebbe had made popular. He stressed them and literally seared these thoughts into our minds. The song completed, we took our leave of him with the same Gut Shabbos with which he had begun the Tish.

He was now alone, in his own room, and most everyone had left. Only a few of us lingered, and we listened. Alone, the Rebbe was dancing a Shabbos song by himself; he was dancing around his own Tish laden with sefarim, singing aloud to himself. No weariness and no exhaustion marred his Shabbos. He sang and danced until the rays of the sun entered his room.

All is quiet but all is not over. His spirit continues to sing and dance in our lives and homes.

Tuesday, April 04, 2006

Shir HaShirim, the Song of Songs, is one of the five Megillos, or Sacred Scrolls, that are part of the Hebrew Bible. It was written by Shlomo HaMelech, King Solomon. It is a timeless allegory of the relationship between Hashem and the People of Israel, in terms of the love between a man and a woman. It is recited on Pesach, the holiday that celebrates the liberation of the Jewish People from slavery in Egypt.

On Shabbos Chol HaMoed, the Shabbat that occurs during the Intermediate Days of the Holiday, [or on the Seventh Day of that Holiday when Shabbat coincides with that day], the reading of the Megilla of Shir HaShirim is incorporated into the services in most synagogues in the Jewish world.

It is most appropriate that this Megilla be read on Pesach, because this is the holiday of Spring, the holiday of the return of life, of creativity, to the world. Its theme is love, the rebirth of which is also symbolized by Spring.

As mentioned above, this Megilla is an allegory for the relationship between G-d and Israel in terms of the love of a man for a woman. The mashal, or the metaphor, focuses on the man and the woman; the nimshal, or referent, is the relationship between Hashem and the People of Israel. According to the Rambam [Maimonides], a twelfth century Torah giant of the Jewish People, the highest form of relationship between a human being and Hashem is the relationship based on love, Ahavas Hashem, even higher than the relationship built on fear or reverence, Yiras Hashem. The Rambam continues, "Just as when a man loves a particular woman, he cannot remove her from his thoughts, with just such intensity should a person love Hashem."

And since Judaism regards the relationship between a man and a woman as potentially holy, Rabbi Akiva argued (Mishna Yadayim 3:5) for the inclusion of Shir HaShirim in the Sacred Canon when its inclusion was questioned because of the apparent earthiness of the mashal. He said that if all the other Books of the Bible are considered Kedoshim, Holy, then Shir HaShirim must be considered Kodesh Kadoshim, the Holiest of the Holy, because both its mashal and its nimshal are holy.

(Adapted from the OU’s “Introduction to Shir HaShirim”)

Another explanation:

…from earliest times the Song of Songs has been interpreted, not as an expression of human romance, but as an allegorical conversation between G-d and Israel. The literal words of the book are simply King Solomon's way of casting deep meanings into poetic and beautiful language. He brilliantly chose the metaphor of love, with all its ramifications---including sexuality---to explain and explore the various aspects of G-d's complex relationship with His chosen people.

Rabbi Akiva himself argued strongly that the allegory was the only way to interpret the book; his famous words are "All the Writings are holy, but the Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies." And that's how it comes to be in the Bible.

Now we see the connection between Shir HaShirim and Pesach: Pesach is the holiday commemorating the awesome physical realization of the relationship between G-d and Israel: the creation of Israel as a people via the Exodus from Egypt, an unprecedented event carried out by G-d personally. So of course the appropriate book to read is the poetic exposition of that same relationship.

And finally, from Rabbi Yehuda Prero of Torah.org:

Pesach is a holiday on which we celebrate our freedom. We were freed from physical enslavement and from spiritual bondage as well. Perhaps it is because of the dual aspect of our freedom that we read Shir HaShirim on Pesach. Once G-d released the nation of Israel from Egypt, they were free to serve G-d with both body and soul. On Pesach, we focus on using our power of speech, which we said is the prime example of the convergence of physical and spiritual. Shir HaShirim contains many praises of the body, the physical. Why is the body praised? Is it because of the aesthetic value of the human form? No. It is because of the spiritual value of the human form, something very physical, something that we often remove from the realm of spiritual. To focus on the newfound freedom that Pesach celebrates, we read Shir HaShirim. This book, the holiest of all, contains the praise that comes when symbiosis exists within ourselves, when our physical body is used spiritually. The unity of physical and spiritual was only possible when we were free from bondage in both realms, a liberation which Pesach commemorates. Because we can now use our physical for the spiritual, we sing the praise of the physical (which is spiritual as well) on Pesach, as Shir HaShirim.

***

The lyrics to Daniel Shalit's Cantata - click to enlarge

All of this is an introduction to my post, which was inspired by a wonderful concert I attended Monday afternoon-evening here in Yerushalayim. The truth be told, in addition to authentic Jewish Negina, I like and listen to a wide variety of music. Over the years, I have gained an appreciation for classical music, and enjoy listening to it, especially to a live performance. Here in Yerushalayim we are blessed with some wonderful opportunities for this – not the least of which is a weekly, free concert of chamber music performed in the Henry Crown Symphony Hall of the Jerusalem Theater, called “Etnachta”. These concerts are also broadcast live on Israel’s classical music radio station, Kol HaMusica [the Voice of Music]. The catch is that these concerts are on Monday afternoons between 5 and 7 pm, and one should really be at the theater by 4:30 in order to get a free ticket.

So, in order to treat my wife and myself to a brief musical respite to the heavy season of Pesach cleaning, this week’s concert really caught my eye: a performance of Max Bruch’s “Kol Nidrei,” Orit Wolf’s “Memories from the Synagogue,” Ernst Bloch’s “Niggun from the Baal Shem Suite,” and a Shostakovich Trio for piano, violin and cello. But the wondrous, beautiful surprise of the evening was a Premiere performance of Daniel Shalit’s Cantata for Tenor and Piano entitled, “HaShirim Asher L’Shlomo – the Songs of [King] Solomon.”

Shalit is an Israeli-born [1940] composer, who also happens to be a philosophy professor and a baal teshuva, and was present in the audience at the concert. A sample of his music (Rondeau, 1972) can be found here. He introduced the Cantata with a brief explanation, and after its performance, came up to the stage to congratulate the performers – Yosef Aridan, the tenor soloist, and pianist Shlomi Shem Tov.

The Cantata begins with a Midrash from the Yalkut Shimoni, explaining how it is that Shlomo HaMelech wrote Shir HaShirim, Mishlei [Proverbs] and Koheles [Ecclesiastes]. “Rabbi Yochanan said, ‘Shlomo first wrote Shir HaShirim, then Mishlei, and then Koheles.’ Rabbi Yochanan’s reasoning is from the way of the world: when a man is young, he sings and writes poems and songs; when he matures, he speaks of wise parables; when he is aged, he speaks of ‘vanities’ ”. The Cantata then goes on to develop these themes, by citing verses from these works of Shlomo’s, all of which is sung or recited.

But then comes the finale – an exhortation to Shlomo HaMelech from an imaginary “chorus” to return the Song to us. Daniel Shalit explained that indeed, Shir HaShirim is the deepest of Shlomo HaMelech’s works – in the words of Rabbi Akiva, “the holiest of the holy.” Indeed, its depths are a pathway to the book of Jewish mysticism, the Zohar, as the Zohar itself says: “Shir HaShirim – the Song of those Sarim [Ministers] Above; the Song that includes all aspects of Torah, wisdom, strength and power, of what was and what will be. The Song which the Ministers Above sing” [Zohar, Shemos 18b].

One can also say that Torah is an unending cycle – as soon as we finish the Torah with Parshas Zos HaBracha on Simchas Torah, we begin it anew with Breishis. The Gemara starts on Daf Beis, to indicate that you never really begin, nor do you end. And in Koheles [1:5] itself we find, “V’zarach hashemesh uva hashemesh – the sun rises and the sun sets,” about which the Gemara [Yoma 38b] says, “A tzaddik does not depart from this world until another tzaddik like him is created [born].”

So, Shalit’s Cantata ends with the chorus exhorting Shlomo HaMelech: “Give us, Shlomo! Give us, return to us, that which you took and divided and cut and investigated and criticized and surrounded and straightened out and tied! Give us back the song and the dew, return the secret of the Shulamis [the complete or peaceful one] to us, and [return] the lions’ dens, and the panthers’ mountains. Teach us the wisdom that is Niggun, teach us the reason for the advantage of Man’s striving! Sing us a Song, give us a Song, a final Song, Shir HaShirim! Give us the last Song, [you] the wisest of all Men – Shir HaShirim!”

Monday, April 03, 2006

Today is the 5th of Nisan, the yahrzeit of Rebbe Avraham Yehoshua Heshel of Apt

The following story is well-known, appearing the sefer Sippurei Chassidim by Rav Zevin, but I have embellished it from other sources, including some from Reb Shlomo Carlebach.

The Sadigerer, Reb Yaakov, used to tell this story on the night before Pesach, at the time of the searching for leaven, Bedikas Chametz:

In a small village near the town of

Many times the nobleman tried to collect the rent, and each time the Jew was unable to pay it. Even threats of violence failed to move the Jew to pay, as he simply didn't the money. Finally, on Shabbos HaGadol, the Shabbos before Pesach, the nobleman sent his “Cossacks” - henchmen - over to the Jew’s house, to show him that he meant business. So what did they do? Well, they poured out sewage water all over the floor, threw the cholent [hot Shabbos stew] out the window, ripped apart all the tables and chairs and literally destroyed everything they could get their hands on.

When the Jew and his family returned to what was left of their house, they were so dismayed, and full of despair and fear, the only thing that the Jew could do to comfort himself, he decided, was to go to Kolbisov to hear the Rav's Shabbos HaGadol drasha [sermon].

Meanwhile, the nobleman of the village wanted to know how the Jew was taking all his misfortunes, so he sent over his henchmen to check up on him. When they discovered that the Jew was dancing and singing for joy, they didn't know what to make of it. They went back and told the nobleman that the Jew had most likely cracked up, under the strain of his troubles.

That night the nobleman sent for his tenant, the Jew. At first he was afraid to go, but then he remembered the words of the Rebbe, that Hashem is redeeming

"Well what can I do?" replied the Jew.

"Okay, Moishke", the nobleman answered, "I'II tell you what I'll do for you. Take this credit slip and bring it to the distillery in Kolbisov, and they will give you some whiskey. With this whiskey you can realize a small profit. With the profit, you can pay the rent you owe me, and also provide for your family’s needs. You can get on credit as much whiskey as you need."

So the Jew did this, and in the few days, between Shabbos and Erev Pesach he sold so much whiskey that he was able, not only to pay part of the rent he owed the nobleman, and to buy for his family all that was necessary for the holiday, but he even had some money left over also.

R. Shmuel Zivan adds: Shabbos HaGadol is the kernel and beginning of the Redemption that comes on Pesach. The Redemption begins when the heart is filled with emuna and bitachon, faith and trust in Hashem, to such an extent, that one is filled with joy, even if the external circumstances are excruciatingly difficult. In this story, we see how this internal change shifts the developments to a new path.

***

The Ohev Yisrael and Negina:

Zechuso Yagein Aleinu v'al Kol Yisrael - May the Ohev Yisrael's merits protect us all!