Sunday, August 27, 2006

Reb Shraga Feivel – A Seething Musical Spirit

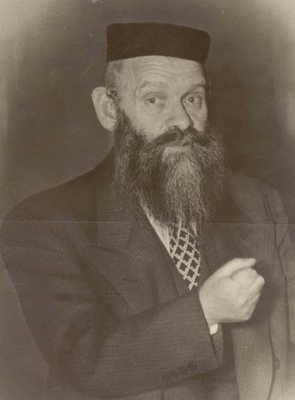

Today is the 58th yahrzeit of the great Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, pictured above.

from Jewish Action

Today, it is not uncommon to find Roshei Yeshiva taking on the role of Rebbe and advisor and Chassidic Rebbeim establishing serious yeshivos that employ first-rate Talmudic scholars; this is due, in all likelihood, to the influence of Reb Shraga Feivel.

from an essay about Rav Nachman Bulman, by a close friend:

“More then two decades ago Rav Rifkin Shlita told me that Rav Bulman z”l is unique in this world. He likened the Rav to Rav S.F. Mendlowitz z”l of Torah Voda’ath in that both carried within themselves the demands and avoda of Chassidus and Mussar. Chassidus, as Rav Rifkin explained to me, requires the individual to go out of “himself” and meet the Ribono Shel Olam [G-d] in a cosmic metaphysical experience, while mussar demands that the person moves into himself and through refining his middos encounter his Creator. Most people can not sustain the dual demands of Yiras Hashem and Ahavas Hashem. Either one recoils in fear, or one runs to embrace b’ahava. But both to embrace with love and withdraw simultaneously out of fear into oneself, is seemingly a contradiction. Rav Bulman z”l [and Rav Shraga Feivel - yitz] lived with the tension of this experience having the emotional and intellectual energy and courage for this mighty spiritual voyage.”

In light of this, R. Shraga Feivel had a tremendous appreciation for Negina, which we’ll describe here.

The following is excerpted from an essay by Yosef ben Shlomo HaKohen, titled “Enlightenment Through Music”. Yosef has a wonderful website, Hazon – Renewing Our Universal Vision.

One of Reb Shraga Feivel's disciples was Yiddel Turner, a gifted musician who played the violin. Reb Shraga Feivel would listen to Yiddel Turner's soulful music with great concentration. And when he was in excruciating pain due to his ulcers, it was often the sweet sounds of Yiddel's violin that provided him with his only relief. At those moments, he would say, "Yiddel, please make sure to be there as well at the moment when my soul leaves the world." And he added, "In those few moments of your playing, I was able to think as deeply as I normally can in six hours."

The highlight of the week for the students in the yeshiva was "Shalosh Seudos" - the traditional third Shabbos meal. There is a custom to begin this meal late Shabbos afternoon, before sunset. When Reb Shraga Feivel was present at the Shalosh Seudos, no talks were given. Instead, beautiful, haunting melodies, both with and without words, were sung. At the head of the table sat Reb Shraga Feivel enveloped in thought, his eyes closed, the students seated around long tables, barely able to see him in the waning light. Never was his influence greater than in those last moments of Shabbos: "We felt as if we were in the Garden of Eden," remembers Rabbi Hershel Mashinsky.

Reb Shraga Feivel was once asked why he did not speak words of "mussar" - ethical and spiritual enlightenment - at Shalosh Seudos. He responded that the songs themselves were the most powerful words of mussar and would have the most lasting impact. His disciples agreed. For example, Rabbi Moshe Wolfson, a disciple of Reb Shraga Feivel, and the current Mashgiach - spiritual guide - of the yeshiva, described the experience of being with his teacher at the closing Shabbos meal: "His Shalosh Seudos was like a "mikveh" - a pool of purifying waters - in which one immersed his entire soul."

One Rosh Hashana, after the afternoon service, Reb Shraga Feivel gathered the students together for an hour of slow singing and restrained dancing to the words of the following prayer: "Therefore we put our hope in You, O Compassionate One, our G-d, that we may soon see Your mighty splendor, to remove detestable idolatry from the earth so that the false gods will vanish entirely, and the world will be perfected through the Almighty's sovereignty. Then all humanity will call upon Your Name, to turn all the earth's wicked towards You."

At the end of the singing and dancing, he said to his students: "You saved my Rosh Hashana for me."

On Rosh Hashana, we yearn for the day when a corrupt and oppressive world will seek spiritual enlightenment through sacred music and song. This yearning is expressed in the words of Psalm 47, which many communities chant before the blowing of the shofar. The psalm opens with the following universal call: "Join hands, all you peoples - shout to the Just One with the voice of joyous song." In the middle of the psalm, the author calls out again to the peoples and proclaims: "Make music for the Just One, make music; make music for our Sovereign, make music. For the Just One is Sovereign over all the earth; make music, O enlightened one!" (Psalm 47:7,8)

Who is the "enlightened one" that is specifically being addressed at the conclusion of the above verse? The classical biblical commentator, known as "the Radak," answers: "Every enlightened person, whether among the People of Israel or among the nations of the world should make music for the Blessed G-d." And he adds: "For the ability to compose songs and melodies is found only among the enlightened ones." The Radak is revealing to us the following insight: Although music has the power to increase enlightenment, the ability to compose music is given to those who are in a certain way already "enlightened." They have a special Divine understanding in their souls which enables them to compose music which will increase and deepen the Divine understanding in the souls of all human beings.

***

Finally, R. Yonasan [Jonathan] Rosenblum has authored a wonderful book titled simply, “Reb Shraga Feivel,” from which the following excerpts were taken:

He used to explain that each of the instruments mentioned in the final psalm -- shofar, psalter, harp, timbrel, stringed instruments, flute, loud-sounding cymbals, and stirring cymbals -- arouses a different emotional response: This one arouses tears, another happiness, and yet another encourages deep reflection. Taken as a whole, the message is that one must serve Hashem with every emotion.

Reb Shraga Feivel was extraordinarily responsive to music. Someone once shared with him one Rebbe’s explanation of the Yiddish expression: “A chazzan iz a nar -- A chazzan is a fool.” The Rebbe had explained that in the upper worlds the courtyard of melody and that of teshuva are located close to one another, and thus the chazzan was a fool for not having jumped from one to the other. Reb Shraga Feivel’s dry comment on this vort: “Whoever said that has no appreciation of music; otherwise he would have realized that anyone who is privileged to enter into the courtyard of melody has no desire ever to leave it.”

When Yiddel Turner played the heartrending “Keili, Keili, lama azavtani, My G-d, My G-d, why have You abandoned me?” on his violin, Reb Shraga Feivel would sit there, his eyes tightly shut and a look of intense concentration on his face. So emotionally wrenching was Turner’s playing for him that it not infrequently provoked one of his ulcer attacks. Yet when he was in excruciating pain, it was often the sweet sounds of Turner’s violin that provided him with his only relief. At those moments, he would say, “Yiddel, please make sure to be there as well at the moment when my soul leaves this world . . . In those few moments of your playing, I was able to think as deeply as I normally can in six hours.” (11) Motzaei Shabbos he often asked Turner to play the Modzitzer Rebbe’s niggun to “Mimkomcha Malkeinu Sofi’a -- From Your dwelling place, our King, appear.” He once told Turner, “Yiddel, I marvel at your playing, but even more do I marvel at the violin itself. How can strings of catgut speak so deeply to the soul?” (12)

***

On the last Simchas Torah of his life, Reb Shraga Feivel sat in the waning light with his talmidim in Beis Medrash Elyon singing the haunting melody of Rebbe Isaac of Kahliv, “Galus, galus, vie lang bist du, Shechina, Shechina, vie veit bist du -- Exile, exile, how long you are; Shechina, Shechina, how distant You are.” He told his students how the Divrei Chaim used to send his Chassidim to R. Isaac, as the Divrei Chaim put it, “to study in the yeshiva of galus HaShechina.” For his students Reb Shraga Feivel was a Rosh Yeshiva in the same yeshiva.

You may be interested in my book, Hearing Shofar: The Still Small Voice of the Ram's Horn, posted at www.HearingShofar.com.

<< Home