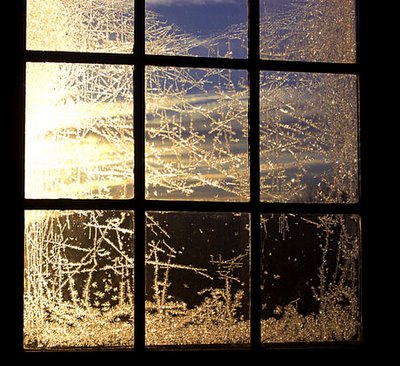

Monday, January 30, 2006

Tonight and tomorrow, the 2nd of Shvat, is the yahrzeit of the Rebbe Reb Zusia of Anipoli, talmid of the Maggid of Mezritch and the younger brother of the Rebbe Reb Elimelech of Lizhensk, who introduced him to Chassidus. He was a great anav [humble person] and had fervent yiras Shamayim – fear of Heaven. His divrei Torah appear in a small sefer called Menoras Zahav [“The Golden Candelabra”]. Reb Zusia is also the forefather of the Hornsteipel Twerski family, who are direct descendants [ben acher ben] of his.

The Rebbe Reb Zusia was always involved in dveykus [clinging to Hashem], in tikkun [rectification] and teshuva [penitence]. He and his older brother, the Rebbe Reb Elimelech, spent several years incognito in a self-imposed exile, to atone for the "sins" of their youth and to improve themselves spiritually.

His intense Ahavas Yisrael – love for his fellow Jew – meant that he would never embarrass others. When he saw someone who needed a tikkun, for example, for lashon hara [improper speech such as gossip], he would say: “Oy, has Zusia sinned today! He said so much lashon hara!” He said this so fervently that those around him who were guilty of lashon hara immediately felt their lack, and did teshuva for it.

Reb Zusia had a notebook in which he would record all of his misdeeds and improper thoughts of the day. Each evening before retiring, he would read through the day’s mishaps, and would cry so profusely that the entire writing would be erased from the tears that fell.

He often would commune with nature, which he preferred to sitting and learning in the beis medrash [study hall]. There he would sing the verses of King David’s Tehillim [Psalms] with a sweet voice and wondrous dveykus, which attracted whomever heard him. Their hard, cold hearts would be softened and responsive to the sweet sounds of the chapters of Tehillim which he sang. His song aroused those who heard it to teshuva…in fact, that was the goal of his song.

The niggunim of others also drew his heart – as long as it was directed Heavenwards. His intense Ahavas Yisrael was also shown towards those who sinned, as evidenced in the following.

One Yom Kippur night, the Jews in the Shul in Anipoli stood covered in their talleisim [prayer shawls]. At the prayer stand was the chazan [cantor], whose voice trembled with the words: “V’nislach l’chol Adas Bnei Yisrael, vla’ger hagar bsocham, ki l’chol ha’am b’shgaga – the entire community of Israel, along with the proselytes who join them shall be forgiven, since all the people acted without knowledge” [Bamidbar 15:26]. The chazan sang these words with a tune that moved the trembling hearts of the congregation towards their Father in Heaven, and filled them with longing and yearning for Hashem.

Then they heard the Rebbe Reb Zusia’s voice sing out to Hashem: “Ribono shel Olam [Master of the World], if the Jews had not sinned, they could never sing such a lofty niggun as this, as they cry out for help. Ribono shel Olam, hear this beautiful niggun, which is full of outpouring of the soul and yearning for You, and forgive the entire community of Israel, who are singing such a lofty tune before You, begging for Your forgiveness.”

Just as teshuva can transform evil into goodness, a niggun can be lifted up from the dirt to become a source of Kedusha [holiness]. Once the Rebbe Reb Zusia passed through a field, where he heard a shepherd, who was tending his flock, play a lovely niggun on his flute. Reb Zusia approached him and listened intently, until he memorized the tune. He then continued joyfully on his way, feeling that he had redeemed a niggun of the Shepherd King David from its long exile.

Zechuso yagein aleinu v’al Kol Yisrael, may the Rebbe Reb Zusia’s merit protect us all!

Friday, January 27, 2006

A note to my readers: as I privately wrote to someone this week, “a man’s Home Page is his Castle.” This is especially so in the world of blogging, where we try to express ourselves and our own personal tastes. While I try to be faithful to the [rather bombastic] title of this blog, "Heichal HaNegina," I cannot help but choose those people and music that I most appreciate and enjoy. An example is found below: although HaRav Hirsch zt"l was not particularly known for his Negina [and I don’t know if he had any niggunim, or even if he could sing], I have a long-standing appreciation of his Torah that he has enlightened the world with. I would consider him one of the Gedolim of the 19th Century in which he lived.

Today, the 27th of Teves, is the Yahrzeit of HaRav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch [1808-1888], known by some as the father of modern Jewish Orthodoxy. Rav Hirsch taught that a Torah-committed Jew could live in modern society by using Torah - the Divine Truth - as the yardstick by which to measure all new ideas and developments. His vast works include his philosophical Horeb and Nineteen Letters of Ben Uziel, and his commentaries on the Chumash [Bible], Tehillim [the Psalms] and the Siddur [prayer book]. He was a staunch opponent of the Reform movement in Germany.

Below are two examples of Rav Hirsch’s writings about Music, taken from his Commentary on the Chumash.

“And his brother’s name was Yuval. He was the father of all those who play the lyre and the flute.” [Breishis, 4:21]

Rav Hirsch explains: “Yuval, the father of all those who play the harp and flute – in other words, Art. In Kayin’s [Cain’s] world, art is just as necessary as industry or handicraft. When Man departed from G-d, inner harmony departed from Man heart. Art seeks to restore Man’s inner harmony through external stimulation. This is especially true of Music, which expresses neither images nor concepts, but only moods and feelings; it presents and awakens feelings and thus sensitizes the soul. Like all fine art, music is a preliminary stage in the education of mankind toward goodness and truth. Music – like Yuval - produces no actual assets, and its existence depends on the support of anshei mikneh [cattle breeders]. In Kayin’s world, Art signifies that Man has aspirations more exalted than the increase of material possessions.”

***

“Yisrael, their father then said to them [his sons]: ‘If it be so, then do this – take from that of which the land boasts [Zimras ha’aretz] in your vessels and bring down a gift to the man [Yosef].’ ” [Breishis, 43:11]

Rav Hirsch comments: “It is very peculiar that, in our language [Hebrew], ‘song’ and ‘tendril’* [zemora*, to be explained below] are designated by words of the same root. There are three words for ‘song’ – shir, niggun and zemer. Shir is song in poetry. Niggun is instrumental music. It is possible that nagen essentially denotes an instrument…Zimra is a melody, the singing of a wordless melody.

“If the foregoing is correct, how does our language regard the relation of melody to song [shir], if melody is called zimra, which is related to zemora, “tendril.” As a rule, it is not foreign to the spirit of our language that phenomena from the realm of thought and speech are assigned terms from the realm of plants…

“If we bear in mind the relationship of zemer with Shomer and tzemer, it becomes clear that the *zemora is a part of the vine where the juices rising in the vine are preserved, blended and refined, so that they are able to produce the fruit of the vine. The fruit does not grow directly on the stem. Rather, the juices flow through sprawling, twisting tendrils* until they emerge as fruit in the berry.

"We find the same relation between the melody and the words of a song. Emotions and perceptions that have not yet ripened in the human spirit, have not yet reached full clarity in thought, have not yet been suited for expression in words, are ripened and clarified on the wings of melody, and in the loftiness of inspiration they find the word. Natural man speaks to others and sings to himself. In true art, which has not distanced itself from nature, the melody is the bearer of the word, the melody’s whole existence is for the sake of the word, and not vice versa…Melody is a gently winding tendril, and on the threads of its tone it presents its fruit: the impassioned word."

Tuesday, January 24, 2006

from the chabad.org website:

The founder of Chabad Chassidism, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), passed away on the eve of the 24th of Tevet, at approximately 10:30 pm, shortly after reciting the Havdala prayer marking the end of the Shabbat. The Rebbe was in the village of Peyena, fleeing Napoleon's armies, which had swept through the Rebbe's hometown of Liadi three months earlier in their advance towards Moscow. He was in his 68th year at the time of his passing, and was succeeded by his son, Rabbi DovBer of Lubavitch.

What follows are some sayings by the Alter Rebbe about Negina, and then a listing – with links – of some of his niggunim.

The tongue is the pen of the heart, but melody is the quill of the soul.

A Niggun can pull one out of the deepest mire.

A Jew is a human being in touch with his inner essence and possessed of the ability to unveil it, and bring it forth. How does one connect with one's inner self, one's highest levels of soul, above all, wisdom and comprehension, and then reveal it in a mundane, finite world? This can be accomplished through song.

[thanks to A Simple Jew for this quote]

Rabbi Dov Ber, the son and successor of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, often used to say, 'My saintly father could penetrate into the innermost recesses of a Chassid's soul by either a word of Chassidus or a niggun.'"

Worth mentioning is another story of the rhapsodic fame and simplicity of niggunim, again involving Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi. A man of unconventional ways, he filled his homilies with folk tales and wise sayings of the Jewish People. One day, as he preached in the shul, he noticed the bewildered look of an old man who was trying hard to get the drift of his words. After he had finished his sermon and the congregation was departing, he said to old man: "I saw by the expression on your face that you did not understand my sermon."

"Yes, you are right, Rebbe," confessed the old man.

The modest Rebbe apologized, saying, "It may have been my fault. Perhaps I was not clear enough. At any rate, I'm going to sing to you now, for melody goes right to the heart and the understanding where words fail." And so he threw his head back, and closing his eyes, sang with ecstasy a niggun, the song of return. As the old man listened his face lit up.

"I understand your sermon now, Rebbe!" he exclaimed happily.

CHABAD MUSIC THEORY

For Chabad, Niggunim were not only an integral part of Chassidism – the songs are a complex philosophy unto themselves. The Chabad system, as first formulated by Rebbe Schneur Zalman of Liadi, strives for the same goal as the other branches of Chassidim, namely the attaining of Divine bliss. But it had, and still has, a unique approach to that goal. Chabad contends that it is impossible to leap immediately from extreme melancholy to extreme joy. It is impossible for a human being to rise from the lowest to the highest state without proceeding through the whole scale of the intermediate sentiments of the soul. Great stress and care is laid upon each progressive stage of development, as significant for the education of the soul and for the improvement of the spirit. It is, Chabad Chassidism contends, as of someone who had never seen the interior of a palace suddenly stepped into its bewildering splendor without first having passed through its corridors. Such a person will never be able to sense fully the glory of the palace. The approach to joy, therefore, is extremely important, and each and every step must be achieved through deep meditation. The various stages in the process of elevation according to Chabad philosophy are:

1) “Hishtapchus Hanefesh”, the outpouring of the soul and its effort to rise out the mire of sin, out of the Klipa, the evil shell.

2) “Hisorerus”, spiritual awakening.

3) “Hispaalus”, the stage in which the individual is possessed by his thoughts.

4) “Dveykus”, communion with G-d.

5) “Hislahavus”, flaming ecstasy.

6) “Hispashtus Hagashmius”, the highest state, in which the soul completely casts away its garment of flesh and becomes a disembodied spirit.

Many of the Chabad songs are analyzed according to these steps of elevation. A system such as this could with much less success than the Beshtian School seek tunes from the outside, because no such program underlay the folk songs of the gentiles. True, one can find among Chabad Niggunim many songs of Russian and Ukrainian origin, often sung verbatim in these languages. By and large, however, these are the shorter and happier melodies of their repertoire. For the achievement of the goals as outlined above, Chabad was compelled to create original tunes which could express the meanings and thoughts of the various stages of elevation, tunes to be used as a means for the attainment of its purpose. Every Chabad tune aims to voice either all, or some, of the stages of elevation of the soul.

The following are attributed to “Sayings of Chabad,” so they are not necessarily from the Alter Rebbe – although they might be:

A person sees himself as he truly is through a Chassidic Niggun.

Song opens a gate from the mind to the heart.

If you sing a Niggun correctly without mistakes then the Niggun speaks for itself.

Every locksmith has a master key with which he can open many doors. Negina is such a key, for it can unlock all doors.

Comparatively of slower movement are the cadre of ten Chabad niggunim [link is in Yiddish] with a distinctive character and temperament of their own, created by Rabbi Schneur Zalman. Although he didn't write the first niggun nor did he write the last one, his ten are greatly revered as the classics of Chabad niggunim the world over.

Niggunim from the Alter Rebbe:

Niggun Three Bavos – from the Baal Shem Tov, the Maggid of Mezritch, and the Alter Rebbe.

Niggun Four Bavos – sung at all Chabad chuppos [weddings].

Keili Ata – from Hallel; I have heard that the Alter Rebbe sang the entire Hallel with this tune. Can anyone verify this?

Tze'ena u'Re'ena; Kol Dodi; Avinu Malkeinu; Niggun Dveykus in Tefillas Shabbos; Niggun Likras Shabbos; Niggun Dveykus Rosh Hashana; K'Ayal Ta'arog; Tzama Lecha Nafshi; Niggun and Bnei Heichala.

A Niggun from the times of the Alter Rebbe; From the Chassidim of the Alter Rebbe

All of these can be found here. You will need the RealPlayer to hear them.

And finally, Shoshanas Yaakov - From Chassidim of Alter Rebbe, with a

Yiddish commentary.

UPDATES: You can find more Chabad niggunim on other locations on the World Wide Web. Among them:

1. There are many Chabad niggunim here. They also have the notes and history behind many of the nigunim. For example here. [from our Anonymous commenter].

2. Another place to find Chabad niggunim is at the Kesser website. Here you will find them in RealPlayer and MP3 formats.

3. Also visit Paul Kornreich's audio gallery of the Rebbe ZT"L singing some Chabad niggunim.

4. Finally, if anyone knows the composer of this Chabad Rikud [Dance tune], please answer in the Comments or e-mail me. Thanks!

Monday, January 23, 2006

Tonight and tomorrow, the 24th of Teves, is the yahrzeit of Rebbe Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the Rav Baal HaTanya, talmid of the Maggid of Mezritch and founder of Chabad Chassidus. He is best known for his sefer “Tanya,” the fundamental source of Chabad Chassidus. When Rebbe Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev first saw this sefer, he remarked, “What an amazing thing Rebbe Schneur Zalman has done! He took an infinitely great G-d and put him into such a small sefer!” At the tender age of twenty-five, he was commissioned by the Maggid to re-edit the Shulchan Aruch, the Jewish Code of Law. The result was a new edition of the Code, known simply as Shulchan Aruch HaRav. It is cited several times by the Mishna Brura, the Halachic compendium authored by the Chafetz Chaim. Rebbe Schneur Zalman also left us Torah Ohr [on Breishis, Shemos and Megillas Esther], Likkutei Torah [on Vayikra, Bamidbar, Devarim and Shir HaShirim] and a Commentary on the Siddur [Jewish prayer book] and the Zohar.

***

The following story is presented with permission of its author, R. Yanki Tauber, of the Chabad.org website. We mentioned last week, from Lazer Beams, that “a niggun (melody) uplifts the soul, puts wings on your heart, and breaks the grip of the vise that the Yetzer [the evil inclination] has clamped on your mouth. After singing a niggun for a few warm-up minutes, the words of personal prayer and love for Hashem will flow forth like a fountain;” to which our friend McAryeh added, “It's true! The power of a niggun to free you from what holds you back is incredible!” But when sung by a Tzaddik, perhaps a niggun can do even more…please read on…

The Mishna quoted in the story is the first Mishna in the fifth chapter of Masechta Shabbos. The Hebrew reads as follows:

...וכל בעלי השיר יוצאים בשיר ונמשכים בשיר...

(a horse in a "Shir" or collar, bridle)

The Master of Song

Told by the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson; translation/adaptation by Yanki Tauber

In the early years of his leadership, the founder of Chabad Chassidism, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, would expound his teachings in the form of short homiletic sayings. It was only in later years (particularly after his liberation from imprisonment in Petersburg in 1798) that he began delivering the lengthy, intellectually profound discourses which characterize the "Chabad" system of Chassidic thought.

One of these early short discourses was based on the Talmudic passage, "All bearers of collars go out with a collar and are drawn by a collar" (Shabbat 51b). The Talmud is discussing the laws of Shabbat, on which it is forbidden for a Jew to allow his animal to carry anything out from a private domain to a public domain; however, it is permitted to allow one's animal to go out with its collar around its neck, and even to draw it along by means of its collar. But the Hebrew word the Talmud uses for "collar," shir, also means "song." Thus Rabbi Schneur Zalman interpreted the Talmud's words to say that, "The masters of song -- the souls and the angels -- go out in song and are drawn by song. Their 'going out' in yearning for G-d, and their drawing back into their own existence in order to fulfill the purpose of their creation, are by means of song and melody."

This was in the early years of the Chassidic movement, when the opposition to Chassidism by many mainstream rabbis and scholars was still quite strong. This latest teaching by Rabbi Schneur Zalman, which quickly spread among his followers throughout White Russia and Lithuania, elicited a strong reaction from his opponents, who complained that the Chassidim have, yet again, employed homiletic wordplay and outright distortion of the holy Torah to support innovations to Jewish tradition. The Talmud, said they, is talking about collars worn by animals, not about the singing of souls and angels! No genuine Torah scholar could endorse, much less propagate, such an "interpretation."

Rabbi Schneur Zalman's words caused a particular uproar in the city of Shklov. Shklov was a town full of Torah scholars and a bastion of opposition to Chassidism. There were Chassidim in Shklov, but they were a small and much persecuted minority, and this latest controversy inflamed the ardor of their detractors. While the Chassidim of Shklov did not doubt the truth of their Rebbe's words, they were hard-pressed to defend them in the face of the outrage and ridicule this latest saying had evoked.

A while later, Rabbi Schneur Zalman passed through Shklov on one of his journeys. Among those who visited the Rebbe at his lodgings were many of the town's greatest scholars, who presented to him the questions and difficulties they had accumulated in the course of their studies. For even the Rebbe's most vehement opponents acknowledged his genius and greatness in Torah. The Rebbe listened attentively to all the questions put to him but did not reply to any of them. However, when the scholars of Shklov invited him to lecture in the central study hall, the Rebbe accepted the invitation.

When Rabbi Schneur Zalman ascended the podium at the central study hall of Shklov, the large room was filled to overflowing. Virtually all the town's scholars were there. Some had come to hear the Rebbe speak, but most were there for what was to follow the lecture, when the town's scholars would have the opportunity to present their questions to the visiting lecturer. All had heard of Rabbi Schneur Zalman's strange behavior earlier that day, when all the questions put to him were met with silence. Many hoped to humiliate the Chassidic leader by publicly demonstrating his inability to answer their questions. In the background, of course, loomed the recent controversy over the Rebbe's unconventional interpretation of the Talmudic passage about animals' collars on Shabbat.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman began to speak. "All those of shir," he quoted, "go out with shir and are drawn by shir." "The masters of song," explained the Rebbe, "the souls and the angels, all go out in song and are drawn by song. Their yearning for G-d, and their drawing back to fulfill the purpose of their creation, are by means of song and melody." And then the Rebbe began to sing.

The room fell utterly silent. All were caught in the thrall of the melody, a melody of yearning and resolve, of ascent and retreat. As the Rebbe sang, every man in the room felt himself transported from the crowded hall to the innermost recesses of his own mind, where a man is alone with the confusion of his thoughts, alone with his questions and doubts. Only the confusion was gradually being dispelled, the doubts resolved. By the time the Rebbe finished singing, all the questions in the room had been answered.

Among those present in the Shklov study hall that day was one of the town's foremost prodigies, Rabbi Yosef Kolbo. Many years later, Rabbi Yosef related his experience to the Chassid, Reb Avraham Sheines. "I came to the study hall that day with four extremely difficult questions -- questions I had put forth to the leading scholars of Vilna and Slutzk, to no avail. When the Rebbe began to sing, the knots in my mind began to unravel, the concepts began to crystallize and fall into place. One by one, my questions fell away. When the Rebbe finished singing, everything was clear. I felt like a newly-born child beholding the world for the very first time.

"That was also the day I became a Chassid," concluded Rabbi Yosef.

The content of this story was produced by Chabad.org, and is copyrighted by the author and/or Chabad.org. If you enjoyed this article, we encourage you to distribute it further, provided that you do not revise any part of it, and you include this note, credit the author, and link to www.chabad.org. If you wish to republish this article in a periodical, book, or website, please e-mail permissions@chabad.org.

Thursday, January 19, 2006

From our friend Lazer Brody at Lazer Beams, a great eitza [piece of advice] if you're stuck in your Hisbodedus. The advice:

Don't fret; here's what to do when the words don't come - sing out a niggun!* A niggun (melody) uplifts the soul, puts wings on your heart, and breaks the grip of the vise that the Yetzer [the evil inclination] has clamped on your mouth (the last thing he wants you to do is to talk to Hashem!). After singing a niggun for a few warm-up minutes, the words of personal prayer and love for Hashem will flow forth like a fountain.

*THE LINKED niggun is none other than Chaim Dovid's "Ya-ma-mai"!

Thanks, Lazer! (The full article is here).

Wednesday, January 18, 2006

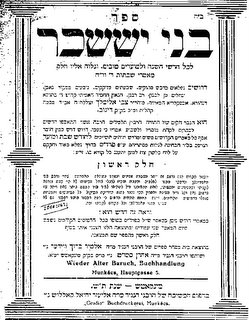

Pre-war [1940] Title Page of the Bnei Yissaschar, published in Munkatch. (Click to enlarge)

We wouldn't be doing justice to the memory of the Bnei Yissaschar without including some stories about him and his music. So without further ado:

When Rebbe Tzvi Elimelech's mother was expecting him, she went to her uncle, The Rebbe Reb Elimelech of Lizhensk, to ask what name to give him.

"You will have a boy, and you should name him Elimelech," was the Rebbe Reb Elimelech's reply.

The woman was astonished to hear this, thinking that the Rebbe was predicting his own demise before the birth of her child (as the custom among Ashkenazic Jewry is to name a child only after people who are deceased).

Noticing her reaction, the Rebbe said, "So name him Tzvi Elimelech," which indeed they did.

After he received the name, the Rebbe Reb Elimelech told her, "If you would have called him Elimelech, all of him would be like me. Now half of him will be like me."

***

Rebbe Tzvi Elimelech grew up to become a talmid of the Rebbe Reb Elimelech's talmid, the Chozeh of Lublin. Once on a journey to visit his Rebbe, he began to ponder his roots - from which Shevet (tribe) of the Jewish People was he descended? And he wondered, "Why is it that whenever the days of Chanuka come, I feel this tremendous increase of Kedusha (holiness), and a wondrous arousal of pleasantness and sweetness? Surely I cannot be descended from the Chashmonaim (the Hasmonean priestly kings, heroes of Chanuka), for I am not a Kohen! So where do these amazing, special feelings come from?

He decided he would ask his Rebbe, who was known as the Chozeh (Seer) because he could see with Ruach HaKodesh [holy spirit, close to prophecy] "from one end of the world to the other."

Upon his arrival at his Rebbe's home, before he could even ask, the Chozeh pronounced, "Your root is from the tribe of Yissaschar, and the feelings of extra Kedusha that you experience on Chanuka is because you were then a member of the Beis Din [court] of the Chashmonaim." For this reason Rebbe Tzvi Elimelech called his opus, "Bnei Yissaschar."

Indeed, he based the name on this verse from I Divrei HaYamim (Chronicles) 12:33 -- ומבני יששכר יודעי בינה לעתים לדעת מה יעשה ישראל

From the sons of Yissaschar, those with a profound understanding of the times so that they knew what Yisrael should do…

***

Rebbe Tzvi Elimelech on Song:

In the sefer Toras HaOlah, the Rama [Rabbi Moshe Isserles] wrote that the Songs the Levi'im sing at the time a Korban [sacrifice] is brought, are like the songs of the Heavenly Hosts above. Whenever a miracle is performed for the Jewish People, where the course of Nature is modified, the Heavenly Hosts cease their Song, and the Jewish People sings. Rebbe Tzvi Elimelech expands this idea as follows.

All of the Heavenly Hosts, the stars, planets and constellations, and all creatures of this World, each of them sings their particular Song according to the qualities they were imbued with by the Creator. The maintenance of all the various forces of Nature depends on their receiving a constant flow of Divine influence and power, uninterrupted. The receptacle for receiving these Divine currents is the unique Song of each one. Therefore, their Song must be uninterrupted...

When there is a miracle where the course of Nature is modified, which causes one of these forces to cease, it automatically follows that its Song also ceases…However, one cannot say that any one of the Songs of Nature completely ceases, and the "Provision of the King" would thereby be lacking…Therefore, the Jewish People, because they are Am Krovo [the Nation close to G-d], make up for the "lost" song by singing Shira.

***

Finally, regarding actual niggunim that Rebbe Tzvi Elimelech may have composed, we have the following information [with slight touch-ups from me] from Nachman from yesterday's post as well as today's:

At the end of a recently-released [edition] of the sefer "HaRebbe Rav Tzvi Elimelech MiDinov, Pirkei Chayav U'Mishnaso" (Fourth edition, 2005, 2 Volumes; compiled by Rav Nosson Ortner, Rav of Lod), there are a few pages of notations of niggunim composed by the Bnei Yissaschar, appearing at the end of volume two. The Kah Ribon, sung at the Tish of the Rebbes of Bluzhev, Toldos Aharon, and Toldos Avraham Yitzchak - is attributed to the Bnei Yissaschar - and can be heard on the first recording of niggunei Toldos Avraham Yitzchak, called "Azamer."

Tuesday, January 17, 2006

Tonight (and tomorrow), the 18th of Teves, is the Yahrzeit of Rebbe Tzvi Elimelech of Dinov, best known for his sefer on Jewish festivals and seasons of the year, "Bnei Yissaschar." He was a nephew of The Rebbe Reb Elimelech of Lizhensk, and named after him; he was a disciple of the Chozeh of Lublin and others...

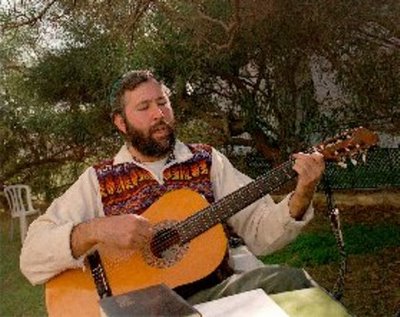

R. Yehoshua Rubin playing his guitar

R. Yehoshua Rubin playing his guitar

I am priviledged to share the following story with you, from R. Yehoshua Rubin, (pictured above) a dear friend and teacher, who himself is a talmid of Reb Shlomo Carlebach zt"l. R. Yehoshua has recorded a CD of a Carlebach Hallel called "Mikimi", and authored some books, some of which can be found here.

Nishmat Kol Chai - The Universal Song

The bench creaked as David rocked back and forth. Sitting in synagogue listening to the cantor mumble away was boring. “Abba, can I go down and talk to Karl?”

“Do you think you will be back for the Rebbe’s prayer?” his father asked.

David sighed “No, probably not.”

His Abba’s kind eyes looked deeply at David when he said, “So what do you think you should do?”

David swung his feet underneath the bench, waiting for the Rebbe to take over the prayer service. Meanwhile he thought about his friend Karl. Karl was his best friend, which was sort of strange in here in Dinov, because Karl wasn’t Jewish. The Jews and non-Jews weren’t really friends even though they were friendly when they met on the fields and in the tavern.

It was different between Karl and David. They were good friends. They spent hours playing, most of it down by the creek that ran through their town. They also talked about everything. It seemed to David that they weren’t so different. Karl’s father bought Karl sweets just like his Abba did and Karl’s father got angry sometimes just like his Abba did. What was really different was their G-d songs. Karl and David taught each other their G-d songs. Karl’s songs were sometimes happy and at times slow and mysterious. David was really surprised when he began to teach Karl his songs.

“You don’t need to teach me,” Karl said, “I know them already.”

David stopped playing with his stick. “You know our songs?!”

“Yeah, sure,” Karl replied with a flick of a twig into the creek. “Your Jewish church is right above our potato fields. Karl, very pleased with himself, continued. “Every week when your Jewish priest sings we hear him so I know all your songs,” and he flicked another twig into the brook.

The tap on David’s shoulder brought him back to the synagogue. “David, stand up for the Rebbe,” his Abba whispered. David didn’t need to be told twice. He loved the Rebbe and he knew the Rebbe loved him. In fact David was pretty sure the Rebbe loved everyone. He once asked him, “Rebbe does G-d love everyone?”

The Rebbe’s eyes shone with fire when he answered, “Of course.”

“Even non-Jews?” David continued.

“Of course,” the Rebbe replied.

David was still troubled. “So how come Jews don’t love all the non-Jews?”

“Maybe because they are not enough like G-d,” the Rebbe said with as sweet smile.

“And why don’t the non-Jews love us?”

David could see the regret in the Rebbe’s eyes when he said, “Maybe it is because they do not know us well enough.”

David saw the Rebbe thank the cantor by grasping the cantor’s hand in both of his. The Rebbe lifted his tallit over his head and the community as a whole breathed deeply as the Rebbe took his first meditative breath. Then the Rebbe began to sing. David closed his eyes as the Rebbe began to sing the prayer known as Nishmat Kol Chai – the universal song.

David had never been to the ocean but he felt that he could almost see it when he heard the Rebbe sing, “If the mouths of all people were filled with song like the sea is full of water, and our tongues as full of joyous song as the sea has waves, we still could not thank You sufficiently, G-d who is in Heaven.”

David imagined that he was in the sky as he heard the Rebbe continue. “And our eyes as brilliant as the sun and the moon, or our hands as outspread as eagles of the sky - we still could not thank You sufficiently, G-d who is in Heaven.”

Karl was waiting outside when synagogue was over. He always waited outside because non-Jews were not allowed in the Jewish church. “Come on David, let’s go play.”

“Sure, sure, but wait I want you to meet our Rebbe.”

“The Rebbe?”

“Yeah, the Rebbe - you know the one who sings.”

“I know who he is, but you know I am not Jewish.”

“So?”

“So he is not going to like me.”

“No, he is not like that - you’ll see”

The Rebbe was standing by the door wishing everyone ‘Good Shabbos’ as they left. After everyone had left David and Karl came up. “Good Shabbos, David.”

“Good Shabbos, Rebbe.”

“Who is your friend?” the Rebbe asked.

David whispered to Karl, “Tell him your name.”

Karl took off his cap, held his hand out and said, “My name is Karl, sir.”

The Rebbe held Karl’s hand with both of his. “Hello, Karl.”

David giggled. “What are you laughing at?” Karl gave David a hard look.

“By us, we put a hat on - not off - to show respect,” David explained.

Karl looked at the Rebbe and said, “Oh, I didn’t know. Sorry, sir.”

“That is quite all right. I am very happy David has such a respectful young friend.”

This became a weekly ritual. Every Shabbat morning, David would walk up the hill with his friend Karl to the synagogue of Dinov. The Rebbe, Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech, would usher David in, wave to Karl who would then run down to join his parents. After synagogue, David and Karl would greet the Rebbe. “I did not think his hands would be so warm,” Karl would always say.

David and Karl’s friendship or the weekly meetings did not go unnoticed, but they were never bothered either. Everyone thought that they would probably grow out of it as they grew up. But that is not what happened. They stayed friends and Karl became the non-Jewish town expert on Jews and Judaism. He taught his brothers and parents the Jewish songs that they kept hearing every Saturday morning in their fields in the valley right beneath the synagogue. Karl took great pride in knowing the identity of the voice the farmers heard every Saturday morning. “That is their Jewish priest; they call him a Rebbe,” he would say, every time - with great pride.

The Rebbe heard rumors about the gentiles singing his songs but he did not know how much the farmers enjoyed his singing, for as they began to hum along with the Rebbe’s soulful prayers, the sun didn’t seem so hot and the plow so heavy. So although they lived their lives apart from each other, it was on Shabbat morning that all the residents of Dinov were as one, as they hummed along with the Rebbe.

Karl lowered his shovel to button his top button, the days were getting colder, and his mother had warned about not catching the illness that was plaguing the town. It was cold. Cold and quiet. Too quiet. Why was it so quiet? Then Karl realized it was Saturday – and the Rebbe was not singing. Karl was waiting outside when synagogue was over. He always waited outside because non-Jews were not allowed in the Jewish church. “David, how come you didn’t sing today?” Karl asked.

David couldn’t meet Karl’s eyes. “The plague,” was all he could whisper.

Karl was worried. “Who? Who is sick? You?”

Teary-eyed, David replied, “No, not me. The Rebbe.”

For weeks the farmers heard no song. The quiet made the wind blow harder and the plow heavier. In fact, the Rebbe never sang the Shabbat prayers again. David and Karl walked right behind the Rebbe’s coffin as it passed through the street of Dinov. All the gentiles lined up in order to pay their last respects to the Rebbe. “You see,” Karl said to David, “I told them to keep their caps like just like you taught me.”

“Thank you, the Rebbe would have been happy,” was David’s muffled reply.

“I will miss him,” Karl said to David.

“We all will,” David replied.

The bench creaked as David rocked back and forth. His feet swung underneath the bench waiting for the Rebbe to take over the prayer service. But he knew the Rebbe was not coming. The prayers would never be the same with out the Rebbe’s voice and his tunes. Where as before Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech’s song would conjure up images of endless seas: “If our mouths were filled with song like the sea is full of water,” and radiant skies: “our eyes as brilliant as the sun and the moon,” now the words seemed so lifeless. David could hear the Rebbe’s voice in his mind: “we still could not thank You sufficiently, G-d Who is in Heaven.”

“But how can I thank G-d now?” David wondered.

Down in the field Karl too had a heavy heart. He thought, “Will they ever sing again? I wish they would sing. They should sing,” Karl thought to himself. “They should sing, this quiet hurts too much.”

But all was quiet. Karl lost himself in the soil. Shovel in, shovel out, turning the soil over and over again. In the rhythm of work Karl found himself humming a tune. He couldn’t quite place it. Yet he knew the tune had words. Over and over he hummed the tune and sang the words.

After a while, he realized that he wasn’t the only one humming the tune. His brothers and sisters were humming along with him, as were his parents. With in a few minutes Karl realized that the whole field was singing the Shabbat morning prayers - the Rebbe’s tunes they had heard week after week.

David got up from his bench and opened the window. His father joined him. The cantor stopped and walked over to the window. Everyone got up to open the windows and listened to the Rebbe’s prayers. “Follow me,” the cantor said. Together they stood outside looking down at their neighbors.

The farmers saw the Jews and stopped their work and their singing. “What is going to happen?” David asked his father.

“I don’t know,” he responded.

“Remember the teaching of the Rebbe,” the cantor began. “The holiness of song is that it breaks down all the barriers between us and G-d and even all the walls between us and our neighbors.”

The cantor began to sing Nishmat Kol Chai – the universal song. “If the mouths of all people were filled with song like the sea is full of water, and our tongues as full of joyous song as the sea has waves, we still could not thank You sufficiently, G-d who is in Heaven. And our eyes as brilliant as the sun and the moon, or our hands as outspread as eagles of the sky - we still could not thank You sufficiently, G-d who is in Heaven.”

And there in the small town of Dinov the Jews and non-Jews were as one as they sang together the Shabbat prayers. As they walked back in inside David wanted to know, “Abba is this what will happen in heaven? We will all sing the prayers together?”

His Abba’s kind eyes looked deeply at David. “What do you think?”

“Abba, I don’t know, but the Rebbe said that the holiness of song is that it breaks down all the barriers between us and G-d, and even all the walls between our neighbors and us.”

Wednesday, January 11, 2006

Thanks to Aish HaTorah for this pic

Thanks to Aish HaTorah for this pic…Vayevarchem bayom hahu leimor, Becha yevarech Yisrael leimor, Yesimcha Elokim k’Efraim vch’Menashe.

The angel who delivered me from all evil, may he bless the lads, and let them bear my name, and the names of my fathers, Avraham and Yitzchak. May they increase in the land like fish…

…And [Yaakov] blessed them on that day saying, “With you shall Yisrael [the Jewish People] bless, saying, ‘May G-d make you like Ephraim and Menashe.’ ”

-- Breishis, 48:16, 20

When we come home from shul on Friday night, we realize that something happened to our house – it’s full of angels. It’s not the same house. You know what angels are? Angels are, first of all, our children – the real angels. During the week, I think that they’re just children. But on Friday night, after I’ve purified my heart – after davening with all my heart, I come home and I realize, “Master of the World, how can I ever thank you for these beautiful angels that you’ve sent into my house?”

Then I say to my children, “boachem l’shalom” – children, when you come into my house, be in peace, let the world be filled with peace. Then, “barchuni l’shalom” – bless me, just because of you let me bring peace to the world, to the Holy Land, to every person. And then, “tzeis’chem l’shalom” – someday, our children will build their own homes. And the deepest question is only, “What am I giving my children on the way?” So I bless my children, someday when you leave my house, please take the Holy Shabbos with you. Do you know what kind of Shabbos I have? I have the Shabbos of my father and my grandfather. And he had the Shabbos of his grandfather, all the way to Moshe Rabbeinu and Avraham Avinu, till Moshiach is coming.

We bless our children, our angels. Rav Kook said that a sign that Moshiach is coming is that every day our children look more beautiful, deeper, sweeter than honey…

Before Kiddush, it’s the holiest custom, every father and mother, puts forth their hands. And even if, maybe, our hands are not shaking, but inside, inside, our hearts are shaking, our souls are shaking. And we’re blessing our children.

According to the great Kabbalists, you’re supposed to say the name of the child, and your name. Because, sadly enough, because Yitzchak Avinu didn’t know whom he was blessing, there was so much pain after that in the world. And we say to our children, “I want to bless you forever!” What kind of man or woman would I like you to be? I’d like you to be like Efraim and Menashe; like Sarah, Rivka, Rachel and Leah.

You know what’s so special about Jewish parents? For us, our children – there have never been such beautiful children in the world! And if you’ll ask me, is there anybody in the world I could compare my children to? Yes – like our holy Avos [fathers] and Imahos [mothers]. And we bless them.

You know, when my father would bless me, he would always sit. And I was a little boy and I would bend my head down, and my father would place his hands on me. I could feel my father shaking. And yeah, you’re supposed to keep your head down. But I’m a little boy, from time to time I wanted to look at my father’s face. And I always saw tears coming down from his eyes. I remember on Yom Kippur night, my father would bless me – a long blessing. The floor was always wet with tears.

So you know, my beautiful children, and all of your children: You know what kind of blessing we give you? We’re giving you the blessings all the way back to Yitzchak, all the way back to Rivka.

For more on blessing the children, see this from Aish HaTorah.

***

The second is the Shloime Dachs version. For an instrumental only rendition, try this.

Once he [Shloime Dachs] called up a young child to sing an impromptu solo during a rendition of Shloime's famous "Hamalach." When the child began singing Dveykus' "Hamalach," without missing a beat, he finished the child's selection and then continued with his own.

Wednesday, January 04, 2006

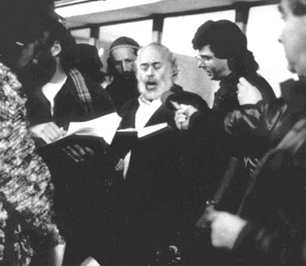

Reb Shlomo Carlebach davening in Leningrad, Russia

Reb Shlomo Carlebach davening in Leningrad, Russia

In last week’s Parsha, Miketz, we find the following:

“And he asked them about their welfare, and said, ‘Is your elderly father, that you told me about, well? Is he still alive?’ They responded, ‘Yes, your servant our father is well, he is still alive [Avinu odenu chai].’ ” Breishis, 43:27-28].

And in this week’s Parsha, Vayigash:

“And Yosef said to his brothers, ‘I am Yosef. Is my father still alive [ha’od Avi chai]?’ ” [45:3]

And in the Gemara [Ta’anis 5b], we find the following:

Rabbi Yitzchak said, “Thus said Rabbi Yochanan: Yaakov Avinu [our father] never died…I learn this from a verse [Yirmiyahu 30:10]: ‘And now, my servant Yaakov, do not fear, says Hashem; and do not be dismayed, O Israel. For I will you save you from afar, and your seed from the land of their captivity.’ He [Yaakov] is compared to his seed. Just like his seed are still alive, so he is still alive.” Rashi explains that Yaakov was brought to Egypt so that he could see his children redeemed before his eyes, and that the verse [Shemos 14:31] that says that “Israel saw the Great Hand that Hashem extended against Mitzrayim [Egypt]”, refers to Yisrael Saba, Yaakov our Forefather.

***

Just about everybody knows the tune, Am Yisrael Chai – Od Avinu Chai. (Please note that there are two links here. The first is a clip of the intro, the second of the song itself. A longer version, but sung by Sam Glaser, is here.)

And many of us know that the words are based on the verses [and Gemara] cited above. And probably most of us also know that this song was composed and sung by Reb Shlomo Carlebach zt”l. But perhaps you didn’t know that it was composed for the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry [SSSJ] in the early 1960s. And even if you know that, the exact story of how it was composed – well, that you probably don’t know. So please read on.

***

Okay – here’s the story we’ve all been waiting for. Please note that from here on are the words of Reb Shlomo Carlebach, [as I’ve transcribed from a tape] - with the exception of some [mostly brief] explanations that I’ve inserted in brackets [ ].

You know friends, I'm sure all of you...You know how many niggunim I made up before I was playing guitar? I made up niggunim all the time, but it was clear to me - no one was gonna sing them anyway. So...I'm sure all of you are making up niggunim, little melodies that come into your head.

But then there are great moments, I have to tell you one of the great moments when I made up (without sounding commercial) one of my best niggunim, "Am Yisrael Chai," you know. Really, they're mamash playing it all over, right?

I wanna tell you the story. You know music is just so good, right? For me, you know, if you want to know who a person is, ask him what kind of music do you like? Simple as it is. Then you know what they're longing for - 'cause music is not what you have, music is what you're longing for. You know what Chassidishe music is? -- touches you so deep! Suddenly it's clear to you - you're longing for something so much deeper, so much holier!

[NOTE: This concept is straight from Modzitz. The first Modzitzer Rebbe, Rebbe Yisrael, said, "When I hear a song from the mouth of a Jew, I can ascertain how much fear of G-d there is within him, and whether he is wise or foolish." -- Melodies of Modzitz, p. 20]

Anyway, I want you to know, in the year 1964, two days before Purim, I gave a concert in Frankfurt [Germany]. And on Purim itself, by the feast of Purim, I was supposed to give a concert in Lyon, in France.

And suddenly I had this crazy idea - why shouldn't I go to the Reading of the Megilla in Prague? You know, some of you - a lot of people today are - but my family also - we are descendants of the Maharal of Prague, the one who made the Golem. And I thought, gevalt, I gotta be there! The only thing is, people tell me in Frankfurt, it's not so simple. At that time, 1964, to go to Prague was the heaviest thing! Even more heavy than Russia. You need a visa at least two months in advance. And, I'll take a chance, it's Purim, right? The Ribono Shel Olam's performing miracles. So I said, "Ribono Shel Olam, what do You care, one more miracle?"

Anyway, listen to this. If some of you know Yankeleh Birnbaum, you know, Yankeleh Birnbaum began working for Russian Jews when it was not the style yet. You know, other people - after there's something happening, they're jumping on the [band]wagon, right? Today, teshuva is the big business, so suddenly everybody is into doing teshuva, right? Not doing teshuva, but making others do teshuva to make money from it. Oh, that's something else, but anyway...

Now, at the time, the Russian Jews were not a money-making business yet. It was mamash for real! [19]64 was the first demonstration for Russian Jews in New York, before Pesach. Anyway, I had a letter in Frankfurt in the hotel, and I'm boarding the plane to go to Prague. When I boarded the plane, they told me, "Do you have a visa?"

I said, "No." They said, "Listen, the plane is there for two hours. If they don't let you in, you [can] come right back." Good.

And on the plane, I'm opening up all my mail. It was stupid. I have a letter from Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. Oy vey! Next to me, you could smell the little KGB man sitting there. And before long he has his nose in my letter. So, I put the letter into my pocket and I walked out to - you know, where the stewardesses, where they serve coffee - and began reading the letter.

In the letter Yankeleh says, "We need a new niggun for this demonstration. I think you should make up a niggun for 'Am Yisrael Chai'."

[NOTE: For the sake of thoroughness, I include here Yankeleh Birnbaum’s side of the story: After initiating the grass-roots movement for Soviet Jewry with the creation of the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry in April 1964, I strove to generate movement songs (now assembled in "Songs of Hope for Russian Jews", originally "Songs of Protest for Russian Jews"). Our dear friend Cantor Sherwood Goffin became the first troubadour of these songs, sang some of them in the Soviet Union in 1970 and recorded some of them in the record "The New Slavery".

I was determined to get one from Shlomo Carlebach. We knew each other and our grandfathers had become acquainted in 1897 at the first Zionist Congress in Basle, Switzerland. His zaide, Rabbiner Arthur Cohn, was Rabbi in Basle and my zaide Dr. Nathan Birnbaum was elected to be the first Zionist Secretary-General.

Shlomo was constantly on the move and hard to pin down. His mother Rebbetzin Paula Carlebach was most helpful in forwarding my requests for a song "Am Yisrael Chai". The request began to resonate with him when he flew to Soviet-dominated Czechoslovakia. Later he told me that he had washed my letter, typed on "Student "Struggle" stationery, down the airplane toilet in some trepidation.]

Arriving in Prague, two days before Purim, and you know in Prague - you think [it's] like today, when you come to the border, you show the passport and you go through. No, the person who's supposed to look at the passport is out, and you end up sitting there for two hours doing nothing. It wasn't the "good old days" in Prague. And we, of a modern kind of society...and you wait. Finally he comes. The man looks at me, he says, "Do you have a visa?"

I say, "No."

"Well, why do you want to go to Prague?"

I don't speak Czech, but they all speak German. I said to him, "I want you to know something. I don't know if you know this, but, about 400-500 years ago, this big Rabbi, in German they call him the High Rabbi Loeb [the Maharal]. And I'm one of his descendants. You know in Prague, in the middle of the city is the monument of the High Rabbi Loeb."

He looks at me and says, "What?! You are a descendant of the High Rabbi Loeb? Do you know something? We're not Jewish, but from the earliest age, from the age 2,3,4,5 - whenever my parents put me to sleep, they would tell me stories of the High Rabbi Loeb." He says, "Here, I'm giving you a visa for five days." Not so simple.

I'm going into Prague, and you know, sometimes people don't tell anybody they're Jewish, but then when they see you, they come out of their hole for a minute. I'm checking in to the Intercontinental Hotel, a good hotel, and the girl at the desk - looks at me about five times - I have a feeling she wants to tell me something. So, I'm hanging around in the lobby, and finally she comes up to me.

"I want you to know that my name is Miriam Levy, and I'm Jewish. I'm so glad to see you, so glad to see you." I wasn't addressed like that in many years.

Anyway, the next morning I'm going to the Alt-Neu [the Maharal’s] Shul, which is now a museum. And everybody knows that the President of the Jewish community is simply a KGB man. Not so simple! I walk in there and I say to him, "I want you to know, I'm a singer. And is it possible that [on] Purim night to get all the young Jewish people in Prague together?"

He looks at me and he says, "First of all, they're not interested. None of our young people are interested in anything Jewish. You seem to forget where you are. And besides, who knows where they are?"

You know, I'm a little bit commercial. I have my [business] cards with me, I put [out] my cards. He sees, "Shlomo Carlebach." He says, "Shlomo Carlebach?!" He got up, came over and mamash hugged me and kissed me. He says, "For nobody in the world - but for you, I'll do it!" I don't know how my cassettes [NOTE: maybe records?] got into Prague. He says, "Do you know that my children play guitar? They're playing your songs day and night. You're their favorite singer!" [At] that time, I had only maybe four or five records.

"And for you I'll do it. My son is at the university - he knows every Jewish student. My daughter is in high school - she knows every teenager. Good, tomorrow night after the Megilla," he says. "Nine o'clock." But he says, "I'm telling you now, the young people are not going to the synagogue." You know why, because in those days, if any boy or girl goes to the synagogue, the next day they're put two classes down. Nebich! Or they don't make it. So they're afraid to go to the synagogue, but he didn't tell me why. "But they'll wait for you outside and take you to a hall."

Okay, I listened to the Megilla reading in the Alt-Neu Shul, and coming out - I don't know, I'll be lying if I [say I] remember exactly - let's say maybe, between forty and eighty young people, aged between 16 and 25.

Okay, listen to this. I was not that much "in tune" yet. There was one boy, his name was George. He's their spokesman. And, a little bit naively, I said, "Why didn't you come into the synagogue?"

So he said, "We're not interested." Good. Then he walks me and he says to me, "Do you know what's going on in America? You may not be aware of it. Young people, completely undereducated. They watch television all day, do nothing, chew gum. The only place for young people really to learn is in Russia, [or] Czechoslovakia."

And I was a little bit stupid, I began arguing with him. I said, "Do you know why you don't have a television? Because you don't have money to buy it! As simple as it is. If you would have enough money, you'd also watch television! And besides, what do you know?"

I argued with him. And he had a big mouth and he says, "There is only one way for the world. Communism is the salvation of the world." He talks very big. Finally, I gave up on him. I walked with other kids.

We come into the hall. And they had a little choir. So it was one song me, one song them - it's Purim night. Do you know something? We sang till 12 - and there were 2,000 walls between us! 2,000 walls! Then I said, "Ribono Shel Olam, Master of the World, it's Purim night. And I'm here to be with them. Ribono Shel Olam, have Rachmanus [mercy] on me."

Suddenly, the door opened. And at that time, there was still an Israeli embassy, before the Six-Day War, there was an embassy. And the Ambassador walks in. And he has with him a bottle of kosher wine. He says (I knew him from before), "Shlomo, I know you're here; L'kavod Purim, I'm bringing you a bottle of wine."

And I was really at my end, I realized that without that - with my head - I won't make it. Mamash I took a big glass of wine, I gave everyone a little bit, I got on the table, and said, "Chevra, I'll tell you something. You know what Purim is all about? That Mordechai is not afraid of Haman. Tonight, I'm not afraid of anybody. I'm not afraid! And I want you to know something. You know what I'm dreaming about? Do you know what you're dreaming about? There's only one thing we're dreaming about - Uvnei Yerushalayim Ir HaKodesh. Every Jew is dreaming about Yerushalayim." And I start singing "Uvnei Yerushalayim" like crazy!

And suddenly, all the walls were gone! All the walls were gone. The kids got up, I want you to know, we danced until 4:30 non-stop. [NOTE: the next sentence was unclear, perhaps it was: I'm crying my eyes out, because none of the kids knew their pain.]

I want you to know, this boy who had such a big mouth before, made his way to dance with me. And he whispered in my ear and he says, "I hope you didn't believe me - what I said. But I want you to know a KGB man was walking with us."

And afterwards I thought, "Oy gevalt, am I far! Gevalt! I know nothing! I know nothing."

We danced like crazy, and it was maybe the holiest night of my life. After that, all those eighty kids walked me to my hotel. I want you to know, until this moment, I still don't know how we did it....I had one pair of tefillin, all the eighty kids…they all put on tefillin, fast: on-off, on-off, on-off, all of them!

You think it was Yom Kippur for me? Hundreds of Yom Kippurs. 'Cause who knows if those young kids will ever have G-d's Name on their forehead? It was awesome! And you know, to put on tefillin on eighty people, it should take a long time? It didn't - it was so fast! 'Cause they had to be [at] 7:30 in school. [At] 6:00 they all left.

I'm here, I was just left in my room. I said to myself, "I can't believe it! I can't believe it! Those kids don't know one word of Hebrew." Just remember, [19]64! And mamash, one Yiddeleh like me comes and they're on fire! So I think I said, "This is a time to make up a song. I gotta make up a song."

It just hit me - Am Yisrael Chai is beautiful, everyone's alive. But Israel without G-d? What's Israel without G-d and what's G-d without Israel? And while making this niggun my tape recorder was working. So I start singing, "Am Yisrael, Am Yisrael, Am Yisrael Chai..."

[Now, back to Yankeleh Birnbaum: He [Reb Shlomo] first sang the song to a group of Prague youngsters. I did not know about this at the time but had continued to press Rebbetzin Carlebach that he should have something ready for our great Jericho march of Sunday April 4, 1965. Late on Friday afternoon April 2nd, my phone rang and Shlomo's exhausted voice said, "Yankele, I've got it for you!"

Jericho Sunday dawned bright and sunny. We encircled the Soviet UN Mission on East 67th Street in New York, Jericho style, to the trumpeting of seven shofars blown seven times and marched to the UN. Shlomo was inspired and for the first time publicly sang what was to become a contemporary Jewish liberation anthem. Even Irving Spiegel, the usually kvetchy New York Times correspondent, basked in the pervasive joyful spirit of the moment.

Shlomo had added another phrase "Od Avinu Chai" with which he climaxed the song on a high note of exaltation. He took this from the Biblical Yosef's exclamation about his father Yaakov… I was pleased that I had worked on Shlomo to create the song.]

PS:

The Arch of Titus

The Arch of Titus

The picture above is of the arch that was built by Titus to celebrate his and Rome's conquest of Israel and the destruction of the Second Temple. The sculpted decorations across the top of the arch portray the Roman soldiers returning in triumph with loot from their destruction of the Temple, especially portraying the Menora which was taken.

Again from Yankel Birnbaum: More than two decades ago, I was approached by someone who felt that Titus' Arch in Rome displaying the Roman removal of the ritual objects from the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 C.E. was a "busha", a continuing shame for the Jewish people, and we should find some way of blowing it up. I responded that the Romans were long gone but we were still here, truly "Am Yisrael Chai". Later, I heard that someone had scratched the term onto the monument as graffiti. I hope it is still there!

From a letter on the Jewish Mailing List, Sept. 2003:

When the Jewish Brigade came to the Arch in 1946, they took red paint and shmeered Am Yisrael Chai on the base of the Arch, again informing the Romans of the past and the present that we were still around. He who laughs last laughs best. We were still laughing at least until about 1970. That's the approximate date of a picture I have in my living room. It's of the Arch of Titus and indeed someone had inscribed, in Hebrew, "Am Yisrael Chai." Whether it's the original Jewish Brigade inscription or, what appears more likely, a continuation of the tradition, can anyone verify if it or a newer incarnation is still there?

PPS: Aish HaTorah’s article about this song, with a quote from Mark Twain.

Sunday, January 01, 2006

is now up. This is a weekly roundup of highlights from all the Jewish blogs. Be sure to check it out at Batya's wonderful site, Shiloh Musings, or at her Me-Ander site. Baruch Hashem, we were blessed with three links from this past week's posts! Thanks, Batya!