Tuesday, January 30, 2007

TODAY'S SEGULA FOR PARNASA

And now, the links:

A PDF file, thanks to A Simple Jew!

For the complete text of Parshas HaMon, from Tefillos.com

Sunday, January 28, 2007

Holding Onto "Above"

From last year's post, The Maharyatz on Negina, updated:

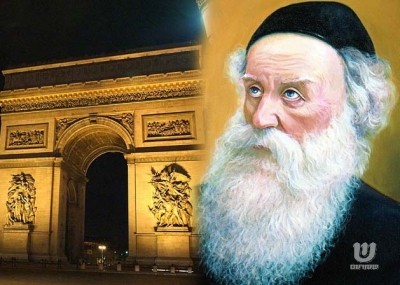

Tonight and tomorrow is Yud [10th of] Shvat, and the 57th yahrzeit of Rebbe Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (1880-1950), the sixth Rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch, who was one of the most remarkable Jewish personalities of the twentieth century. In his seventy years, he encountered every conceivable challenge to Jewish life: the persecutions and pogroms of Czarist Russia, Communism's war on Judaism, and melting-pot America's apathy and scorn toward the Torah and its precepts. The Rebbe was unique in that he not only experienced these chapters in Jewish history -- as did many of his generation -- but that, as a leader of his people, he actually faced them down, often single-handedly, and prevailed.

***

Both Chabad-Lubavitch and Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach are well-known for their pioneering efforts in Jewish outreach, "kiruv rechokim." But what may not be so well-known is that Reb Shlomo was actually the first Chabad shliach [emissary], way back in 1949. With this in mind, I bring you the two stories below, which are strikingly similar. It is highly probable that Reb Shlomo heard the first story from the Maharyatz himself. [I did some light editing on all that follows].

***

From the book, Likkutei Dibburim, by the Maharyatz:

During the winter of 5663 (1903), when I accompanied my father for the couple of months he spent consulting medical specialists in Vienna, he would sometimes go out in the evening to visit the shtiblach of the local Polish Jews – to be among Chassidim, to hear a story from their mouths, to listen to a Chassidic vort, and to observe fine conduct and refined character.

One Wednesday night, on the eve of the Fifteenth of Shvat, my father visited one of these shtiblach, where several hoary Chassidim were sitting around together and talking. As my father and I drew nearer, we heard that they were telling stories of the saintly R. Meir of Premishlan.

Among other things, they related that the mikveh in R. Meir's neighborhood had stood at the foot of a steep mountain. When the slippery weather came, everyone had to walk all the way around for fear of slipping on the mountain path and breaking their bones - everyone, that is, apart from R. Meir, who walked down that path whatever the weather, and never slipped.

One icy day, R. Meir set out as usual to take the direct route to the mikveh. Two guests were staying in the area, sons of the rich who had come somewhat under the influence of the ''Enlightenment'' - of the Haskala movement. These two young men did not believe in supernatural achievements, and when they saw R. Meir striding downhill with sure steps as if he were on a solidly paved highway, they wanted to demonstrate that they, too, could negotiate the hazardous path. As soon as R. Meir entered the mikveh building, therefore, they took to the road. After only a few steps they stumbled and slipped, and needed medical treatment for their injuries.

Now one of them was the son of one of R. Meir's close Chassidim, and when he was fully healed, he mustered the courage to approach the tzaddik with his question: Why was it that no man could cope with that treacherous path, yet the Rebbe never stumbled?

Replied R. Meir: ''If a man is bound up on high, he doesn't fall down below. Meir'l is bound up on high, and that is why he can go up and down, even on a slippery hill."

***

The Maharyatz [R], his son-in-law, Rebbe Menachem Mendel. On the upper left is R. Eli Chaim Carlebach, R. Shlomo's twin brother.

***

After the brothers became Bar Mitzva, they resolved never to touch their beards. Their mother told them that they looked less like proper Rabbis and more like goats. After they arrived in America, the boys went to see the Rebbe Rayatz. Seeing them, the Rebbe said, "I see the results of our work in the external appearance. Now we begin to work on the inside." Years later, the Rayatz observed in a letter to Reb Naftali [Reb Shlomo’s father], "We have taken in the neshamos (souls) of OUR sons." The old Lubavitcher Rebbe accomplished his dream of turning Reb Shlomo and his brother into Chassidishe Yidden.

On Rosh Hashana, the Rebbe Rayatz observed "taanis dibbur" (not to speak, except for matters of holiness). Nevertheless, Reb Shlomo noticed that the Rebbe's lips never stopped moving, the whole day, even at the table. When he asked, Reb Shlomo was told that the entire day of Rosh Hashana the Rayatz would repeat Sefer Tehillim in its entirety, by heart.

The only photograph seen in the apartment above the Shul in New York was the Rebbe Rayatz's likeness, which was prominently displayed both behind Reb Shlomo's chair at the Tish as well as in Reb Shlomo's humble room.

***

From the book, Holy Brother, by Yitta Halberstam-Mandelbaum

In 1949 Shlomo Carlebach's destiny was irrevocably altered when he received a summons (together with his friend Zalman), from the Friehardiger (literally early, meaning previous) Lubavitcher Rebbe. "It was Yud-Tes Kislev (the 19th of Kislev), in December," Zalman recalls, ''and Shlomo and I were inside 770 (Lubavitch headquarters), standing in the corridor near the Rebbe's study. Suddenly, the door opened and Berel Hashin, one of the Rebbe's assistants, waved us into the inner sanctum. 'The Rebbe wants to talk to you both,' he whispered. The Rebbe looked at us and said incisively without preamble, 'Kedei eir zolt onheibein foran tzu colleges (it's time for the two of you to start visiting college campuses).' At this point in his life, Shlomo had never done college outreach before, although he had organized a learning group geared towards people of limited Jewish backgrounds called TASGIG (Taste and See that G-d is Good). I had done a little outreach work previously at Brown University, and also was teaching United Synagogue Youth people, but we were both wet behind the ears. The Rebbe suggested Brandeis University for our first foray, and we collected thirteen pairs of tefillin to distribute at a Chanuka party scheduled to be held in the campus cafeteria.

"I'll never forget that day,'' Zalman chuckles. ''We walked up an icy stairway to the campus cafeteria where a 'Chanuka Dance' was in progress. When Shlomo and I walked in, laden with packages, the music came to a halt and everyone just stared at us, two Lubavitcher Chassidim with yarmulkes, beards, and tzitzis. We divided up the cafeteria like two generals: 'You take the right side, I'll take the left!' and we started doing our thing. Shlomo began telling Chassidic stories, and I started speaking about Jewish mysticism. Soon we were totally surrounded by enraptured listeners, and we didn't leave until two o'clock in the morning.

As we prepared to depart the way we had come in - an icy stairway that had been transformed into a slippery slope - someone yelled after us, 'Hey, there's an easier way out that isn't icy; you'll slip and fall and break your necks if you go down those steps.' For some reason, we disregarded the warning, and descended the steps easily, without incident. Watching our easy descent, a couple of kids tried to follow us, only to slip, slide, and topple down the icy stairs.

'Hey, how'd you manage to navigate the stairs without falling?' one student asked us in astonishment, after he watched his friends' precarious plummet, With a wink and a grin, Shlomo answered, 'Az men halt zich oohn oiven, falt men nisht hinten: If you hold on to Above, you don't fall from below.' "

Zechuso Yagein Aleinu – May the Maharyatz’s merits protect us all!

Tuesday, January 23, 2007

Rebbe Moshe Leib's Intense Love of the Jewish People

***

Brod, Poland, Rebbe Moshe Leib's birthplace, was known as a city of intense Torah scholarship. The term "Ziknei Brod", elders of Brod, was synonymous with wise and elderly Torah sages of the highest order. Yet even the Ziknei Brod were impressed by Rebbe Moshe Leib's Torah knowledge, and asked him what his secret is. How did he get to be such a great talmid chacham?

He answered with a story.

"When I was a young student of the Rebbe Reb Shmelke of Nikolsburg," he told, "I would always want to accompany him when he went to visit his Rebbe, the great Maggid of Mezritch. Every time I would beg him to take me along he would always push me off. I'm too young. I'm not ready. Finally, I heard that the Maggid of Mezritch was on his deathbed. I decided, that's it. I'm packing a bag and going to Mezritch to see the great tzaddik.

When I got to Mezritch I saw throngs surrounding a little house. People told me that that the Maggid is inside and that no one is able to enter to see him. The one exception is that he will reply in writing to someone who writes in a Halachic question. I quickly made my way to the house, came up with a Halachic question and sent it inside. Not long afterwards, my piece of paper came out with an answer on it. I thought a little and then wrote in a question on the Maggid's psak (Halachic ruling) and sent the paper back in. I got a reply from the Maggid refuting my problem. Against that also I had an objection, wrote down my question, and sent in the paper. The Maggid once again replied, but, of course, I had a question on that too. But this time, the Maggid said to his attendants, "Send this fellow in. What does he want from me?"

I entered the Maggid's little house, where he was lying on his bed, and he asked me, "Young man, how exactly can I help you?" I replied, "Rebbe, please teach me; how does one attain 'mochin' (the highest level of Torah understanding and connection with G-d)?"

He said to me as follows: "I'm going to tell you a story. If you don't understand well enough I'll tell it to you again. If you still don't, I'll tell it a third time. But I don't have the strength for more than three times." And this was the story:

There were once two very close friends, young men living in Eastern Europe who did everything together and shared everything. Their friendship was so close that they made a pact that each would always stick out his neck for the other, through thick and thin. Each was willing to give up his life for the other. As life goes, as the years went on they eventually parted paths. One remained in Eastern Europe while the other moved to Italy, becoming an important minister in the Italian king's government.

The one who remained in Eastern Europe fell on hard times and eventually reached a level where he realized he would have to beg in order to get together enough money to support his family. He decided to try one last thing. Maybe the friend of his youth would remember him and help him out. His plan was to approach him as a common beggar. If he recognizes him, wonderful; if not, his will be the first small donation of his stint as a beggar. He took leave of his wife and family, and began his journey to Italy. When he reached the Italian capitol it was near evening already so he took refuge with the rest of the beggars in a room they had for them in the thick city wall.

Well that night, the Maggid continued the story, someone stole a gem from the king's crown, a treasonous crime with a death penalty attached to it. The king's police searched all throughout the city but the gem was nowhere to be found. Because he was the only foreigner in town at that time the poor Eastern European was arrested and accused of the crime. Despite all of his protests, he was swiftly sentenced to death and a public hanging was scheduled for the following day. A gallows was set up on a platform in the town square, and near it a dais was a throne for the king and places for dignitaries. Word got around and early in the morning people gathered for the public execution. In the middle of the town square, prominently displayed on the platform, was the accused.

The accused's friend, the Italian minister, left his estate to his daily activities and noticed the crowds that had gathered in the town square and asked what all the excitement was. "Haven't you heard," people said to him, "That foreign beggar stole one of the gems off the king's crown! There he is in the middle," and they pointed to his boyhood friend -- who he recognized instantly. Right away the minister rode his horse through the square and the crowds parted for him until he reached the king's throne.

"I must admit!" he told the king. "I stole the gem! I cannot let an innocent man be killed." The king was shocked at this admission, but was shocked even more when he heard the accused -- until now claiming innocence - shout out, "OK, I admit. I did it! I stole the gem." Until now the one accused prisoner had denied any guilt, and now both his trusty minister and the prisoner each claimed to have stolen the gem.

"What's going on?" asked the king to his minister. The minister replied, "The man you're accusing of treason is the dearest friend of my youth. We were so close, that we made a pact that each would be willing to give his life for the other. We've been separated for years, but when I saw him ready to be hung I did whatever I could to try and save his life. I know him and am sure that he could not possibly have committed the crime." "And you?" asked the king to the accused. "When I heard my friend call out his admission, the only way I could think of saving his life was to falsely admit the crime myself."

The king was overcome by emotion and looked at the two. "Is there room for a third member in the pact between you. I too would like to become part of this pact of deep friendship."

The Maggid finished telling the story and turned to me. "Did you understand it or will I have to repeat it again?" I asked in the affirmative and he mustered up his strength and repeated the story for me. I would have asked him for a third time but I had rachmanus (mercy) on him because of his health. But I'll tell you, had he told it over to me a third time I would be a much greater talmid chacham today.

The Rebbe of Bohosh (of the Rizhiner dynasty) explained: "Love your neighbor as yourself, I am Hashem your G-d," says the Torah (Vayikra 19:18). Where there is real love between people, there My Presence will be found, says G-d. Knowledge of G-d, understanding His revelation through the Torah, is only possible where there is deep love of people. The King wants to join with those who are willing to sacrifice for their friends. Where there is real love of Israel, there is real Torah knowledge. (Heard from R. Yirmiyahu Friedman of Yerushalayim, who heard it from his uncle, the Rebbe of Bohosh).

FLABBERGASTED!!!

I don't really understand, but I was nominated [thanks, Batya!] for "Best Jewish Culture Blog," and here are the results:

Emes Ve-Emunah

Nominee (Winner in other category) - 4.31

Heichal HaNegina

Gold Winner - 4.29

The Fly Fishing Rabbi

Nominee (Winner in other category) - 4.13

Yutopia

Silver Winner - 3.61

Blog in Dm

Bronze Winner - 3.59

I think it's really a quirk in the system, in that you could have a very small amount of votes, but win because your average "rating" was high. I guess that's a vote for quality [of posts] rather than quantity [of readership], which just might keep this blog going! Thanks!

Sunday, January 21, 2007

Stoking the Holy Fires of Divine Service

Last year’s post: The Rebbe Reb Zusia and the Niggun of Forgiveness.

*****

Stoking the Holy Fires of Divine Service

For three years, the Rebbe Reb Zusia of Anipoli remained in the great Maggid's Beis Medrash and forgot about the entire world - including his wife and children at home. He couldn't imagine leaving this Heaven on Earth. One day, the Maggid reminded him that it was time to go home.

On his way back, he visited his brother, the Rebbe Reb Elimelech of Lizhensk, who had yet to "taste" Chassidus.

Young Reb Zusia spent much of his time in contemplative isolation in the forests, singing praises to Hashem. Even with his brother, he seemed absorbed in his thoughts. When his brother questioned him about his ways, the Rebbe Reb Zusia responded with a parable:

There was once a great, wise king who was beloved throughout his kingdom. A wealthy plantation owner had a burning desire to serve the king. He sold everything he owned, went to the king's city, and tried to find work in the palace, where he could see the king whenever he wanted.

The only job available was that of an oven stoker, who heated the palace. Although this position was one of the lowest, it required the king's approval. Using his wealth to bribe the appropriate officials, the man got the job.

The only job available was that of an oven stoker, who heated the palace. Although this position was one of the lowest, it required the king's approval. Using his wealth to bribe the appropriate officials, the man got the job.That winter, he took special care to provide steady, even heat. The king took notice of this and summoned the man to him, asking him how he could reward him for his faithful, dedicated work.

"I am not looking for financial reward, for I have sold all my possessions out of my love for the king. Indeed, my only goal is to serve the king. My only wish is to be able to see the king whenever I'd like; this is worth more to me than anything," was his reply.

While the king was delighted with his new subject’s deep admiration, he could not fulfill the request. "I'm sorry, but my servants cannot come to me whenever they wish. However," the king continued, "above my room is an attic. You may go there and drill a hole in the ceiling, and whenever you desire, take a telescope and look at me, and no one else will see you." Delighted, the oven stoker did just that.

Shortly thereafter, the prince was banished from the king's presence for one year, because he spoke foolishly at a royal banquet. Eventually, the prince discovered the oven stoker's telescope in the attic, and, longing for his father, he, too, peered into it.

"Woe to you, prince," said the oven stoker. "I am but a common, unlearned person, and I have no other way of seeing the king. But you, his son, should be seated right next to him. You only need to be careful with your words."

As he finished the parable, the Rebbe Reb Zusia told the Rebbe Reb Elimelech humbly, "You know I have neither Torah nor wisdom, and I must slave to see the splendor of the Shechina [Divine Presence]. But you, a great scholar, need only be careful with your words - Torah and prayer - to be seated next to the King of Kings, and to behold His Presence."

Inspired by this story, the Rebbe Reb Elimelech, too, journeyed to Mezritch and became one of the Maggid's prominent pupils.

*****

The above story was adapted from The Maggid of Mezritch, and expanded upon. There is another version of this story in R. AJ Twerski’s book, “The Zeide R. Motele.”

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

THE RAV BAAL HATANYA AND NAPOLEON('S MARCH)

This past Motzaei Shabbos and Sunday, the 24th of Teves, was the 194th yahrzeit of Rebbe Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the Rav Baal HaTanya, talmid of the Maggid of Mezritch and founder of Chabad Chassidus. He is best known for his sefer “Tanya,” the fundamental source of Chabad Chassidus.

We posted twice on his yahrzeit last year: THE Baal HaTanya's YAHRZEIT - THE MASTER OF SONG and Quill of the Soul: Negina of the "Alter Rebbe" of Chabad. Please be sure to read up on them again.

This year, I’d like to present a fascinating account of the Baal HaTanya’s adventures with Napoleon, including the origin of the Chabad-adapted niggun, “Napoleon’s March.” The following is an edited version from various sources that I found on the Web. However, the main source I had found a number of years ago and was unable to relocate it – perhaps it has been taken down. It appears to be from this book: A Day to Recall, A Day to Remember by Sholom DovBer Avtzon. The article has extensive footnotes, some of which I have integrated into the story below. My other sources were Is Judaism a Theocracy? by Yanki Tauber; The Passing of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi; and Bonaparte and the Chassid.

So without further ado, on to our story.

***

There was no more time to lose. Anticipating Napoleon's evil designs to attack and conquer Russia, the Rav Baal HaTanya, (the Alter Rebbe) instructed his family to be ready to flee at a moment's notice. He emphasized this by saying: "I prefer death than to live under his rule. I don't want to be a witness to the calamity that will befall my nation."

The Alter Rebbe said, "Napoleon is a very powerful evil force [klipa], and I fear that I will have to have mesiras nefesh (sacrifice my soul) in order to humble him." What did Napoleon represent, and why did the Alter Rebbe loathe him to such an extent? In every country Napoleon conquered, he introduced the (French) Declaration of the Rights of Man, which abolished serfdom and guaranteed religious tolerance. Understandably, oppressed people everywhere considered him a liberator, and many openly assisted him in overthrowing their rulers.

Many of the extremely oppressed Jews at that time were also taken in by Napoleon. Until then, they'd been restricted from engaging in many occupations; they had to pay a special Jewish tax and were forced to live in ghettos. Napoleon promised to change all that. So they, too, assisted Napoleon and were of great help to him in his conquest of Poland.

Once Napoleon captured most of Europe, he set out to conquer Russia as well. On Tisha B'Av 5572 (1812), he invaded Russia, expecting to receive assistance from the Jews there. The Alter Rebbe marshaled his Chassidim against Napoleon. Why? Because the Alter Rebbe believed that even though Napoleon was good to the Jews (that is, he gave them equal rights and abolished the tax on Jews), and under his regime, the financial and political situation of the Jews would (probably) improve; the Alter Rebbe also foresaw that the spiritual level of the Jewish community would be greatly harmed were Napoleon to gain control over Russia. He expressed it thus: “This is what Heaven showed me during Musaf on the first day of Rosh Hashana. If [Napoleon] Bonaparte is victorious, then the power of the Jews will be elevated, and they will have plenty of riches. However, their hearts will become separated and alienated from their Father in Heaven.”

The Alter Rebbe also said that when the Czar won, he would definitely remember everything the Jews did to help him win the war. Not only would he rescind some of the harsh and harmful decrees that had been set forth against the Jews, but he would also help to improve their situation. This actually came to pass: The Rebbe's contribution to Russia's victory was recognized by the Czar, who awarded Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s descendents the status of "an honorable citizen for all generations." Shortly afterwards, the Mittler Rebbe [his son] received from the government some tracts of land in the Cherson province to establish Jewish settlements. Subsequently, five generations of Chabad Rebbes were to make use of this special standing in their work on behalf of the Jews of Russia.

Thus, the Alter Rebbe prayed constantly for Napoleon's downfall. But there were also rabbis and Chassidic Rebbes who eagerly awaited liberation by Napoleon’s armies. No longer would the Jewish people be locked into ghettos and deprived of their means of earning a livelihood; no longer would the state be allied with a religion hostile to the Jewish faith. Liberated from the persecution and poverty that had characterized Jewish life on European soil for a dozen centuries, the Jewish people would be free to deepen and intensify their bond with G-d in ways previously unimaginable. Indeed, there were those--such as the Chassidic masters Rebbe Shlomo of Karlin; Rebbe Yisrael, the Maggid of Kozhnitz; Rebbe Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev; and Rebbe Menachem Mendel of Riminov--who believed that a French victory would ready the world for the coming of Moshiach and the final redemption.

Since these tzaddikim disagreed about who should win, Chassidim relate that the Heavenly court decreed that whoever would blow the shofar first on Rosh Hashana, his opinion would prevail. The contest was between Rebbe Schneur Zalman and the Maggid of Kozhnitz, and it would decide the outcome of Napoleon’s war against Russia. According to Kabbalistic tradition, the sounding of the shofar on Rosh Hashana effects G-d’s coronation as King of the Universe and the Divine involvement in human affairs for the coming year; each of these two Rebbes therefore endeavored to be the first to sound the shofar in the fateful year of 5573 (1812-1813) and thereby influence the outcome of the war. The Maggid of Kozhnitz arose well before dawn, immersed in the mikveh, began his prayers at the earliest permissible hour, prayed speedily, and sounded the shofar; but Rebbe Schneur Zalman departed from common practice and sounded the shofar at the crack of dawn, before the morning prayers. "The Litvak (Lithuanian, as Rebbe Schneur Zalman was affectionately called by his colleagues) has bested us," said Rebbe Yisrael of Kozhnitz to his disciples.

In addition, the Baal HaTanya sent letters to many Jewish communities, urging them to aid the Russian army in every way possible; encouraging them not to be dejected or pay attention to the victories of Napoleon, as they were only temporary. The final and complete victory would be the Czar's. Secretly, he even instructed his Chassidim to spy against Napoleon's army. His youngest son, Reb Moshe, who was fluent in French, also heeded this call. He moved to the city of Dasvia, where the French army headquarters were located. There, he offered his services to the French high command. They eagerly accepted Reb Moshe, who assisted them by making maps of the routes that the French army should take, and translating all the information that the local villagers gave in their native tongue of Russian, Latvian or Polish. In no time, Reb Moshe gained the French generals' trust.

His task was made all that much easier because the area in which the French army found itself fighting was made up of former Polish provinces. Naturally, the French assumed that the Jews living there would regard them as liberators as the Polish Jews had, and would similarly come to their aid, as indeed, some Jews did. Never did they suspect that the Jews in this area would be disloyal. Although Napoleon was well aware of the Alter Rebbe's tremendous opposition to him, he did not realize the amount of effort the Alter Rebbe expended to ensure his downfall, and to what extent was his influence. Acting as a spy, Reb Moshe was able to pass all his military information to the proper Russian army channels.

The Alter Rebbe wanted nothing less than a total collapse of Napoleon's power. The Mittler Rebbe noted in a letter, "My father's wishes will be complete when [Napoleon's] own countrymen rise up against him." (Indeed, shortly after returning to his own country from his shameful defeat, Napoleon was banished from France).

In the Rav’s eyes, the French leader was the greatest threat to the heart and soul of Judaism. Napoleon's arrogance and free spirit were a denial of the Torah's holy principles of life. Behind his abolishing the restrictions that existed was a veil hiding his true intentions. All Napoleon wanted to accomplish with his revolution, insisted the Alter Rebbe, was a refusal to accept any authority, including belief in G-d's rule. This in turn would weaken one's religious adherence. For this reason, the Alter Rebbe refused to live in Napoleon’s conquered domain for even a short period of time. When he heard that the French army was rapidly approaching, he reluctantly fled Liadi, even though the constant traveling was not good for his health.

NAPOLEON’S MARCH:

When the Alter Rebbe heard the marching song of Napoleon's army, he said it was a (song and a) march of victory. He then decided that the song should be used in one's service to Hashem. [On Yom Kippur, before the shofar is blown (at the end of Tefillas Neila), it is customary in Lubavitch to sing Napoleon's March.] We should note that the Alter Rebbe took away from Napoleon his victory march, elevating it for one's service to Hashem, while Napoleon, as related below, was unsuccessful in his tireless attempts to obtain something of the Alter Rebbe's.

You can listen to Napoleon’s March here; or watch a video here.

Our story continues:

With the assistance of the Russian army, the Rebbe and his entire family began their flight, loaded on four wagons, on Erev Shabbos, 22 Av, 5572 (1812). Before leaving, he instructed the townspeople to help themselves to his furniture and utensils and to make sure to remove everything that was in his house. After traveling approximately two miles, the Alter Rebbe asked the commander for a fast carriage and horses. Together with two attendants, he returned to Liadi and instructed them to search the house for anything that might have been left behind. After a thorough search, they found a pair of worn-out slippers, a sieve, and a rolling pin in the attic. Not wanting Napoleon to obtain any memorabilia from him, the Alter Rebbe took these objects with him. Chassidim insist that the Alter Rebbe thought that Napoleon was a sorcerer, and if he would have gotten hold of anything that belonged to the Alter Rebbe, he would have used it to guarantee his victory (or in the least, to mitigate against the Alter Rebbe's ability to oppose him). Then he told his attendants to set fire to the house, and they left.

This was not a second too early, as immediately afterwards, Napoleon's soldiers entered the city from the opposite direction. Despite their utmost efforts, they were unsuccessful in putting out the fire. All that was left of the Rebbe's house were smoldering ashes. In Napoleon's name, the French soldiers proclaimed that anyone who would give them something that had belonged to the Alter Rebbe would be richly rewarded with gold coins. Obeying the Alter Rebbe's wishes, no one gave them anything. In their anger, the French soldiers burned down the shul that was adjacent to the Alter Rebbe's former house. The Alter Rebbe had foreseen this, and before leaving had instructed the townspeople of Liadi to remove everything from the shul before Napoleon's arrival there.

In the meantime, the Alter Rebbe rejoined his family and the Chassidim, and they continued their flight from the French army. Half an hour before Shabbos, they managed to reach a safe haven, and they remained there in the village until Motzaei Shabbos. Promptly, he continued his flight, hoping to reach a Jewish community in the province of Poltava before Rosh Hashana.

The rapid advance of Napoleon's army made it virtually impossible for the Alter Rebbe and his entourage to rest, and he was forced to be constantly on the run. Some cities were captured by the French barely a few hours after the Alter Rebbe had left them. In one instance, he told his son, HaRav Dov Ber (the Mittler Rebbe), that they should continue their flight on Shabbos as it was a question of pikuach nefesh [survival]. Unfortunately, the entourage made a wrong turn, which put them dangerously off schedule in addition to having to travel an extra distance in the freezing weather.

The Mittler Rebbe wrote: "On Erev Rosh Hashana, my father, the [Alter] Rebbe, confided to me: 'I am extremely pained and worried about the battle of Mazaisk [in history books it is referred to as the battle of Borodino], since the enemy is becoming stronger and I believe he [Napoleon] is also going to conquer Moscow.' He then wept bitterly, with tears streaming down his face.

"On Rosh Hashana, my father again called me to him and happily told me the sweet and comforting news: 'Today, during my prayers, I had a vision that the tide has changed for the better and our side will win. Although Napoleon will capture Moscow, he will eventually lose the war. This is what was written in Heaven today.'" On that day, the battle of Borodino began. It was the first time that the Russian Army openly engaged the French in a battle, and they inflicted great losses upon them. We should note that the battle began in the early morning, at approximately the time that the Alter Rebbe blew his shofar.

The Mittler Rebbe continued: "That day we ate and drank in joy and happiness, in good spirit - rejoicing with gladness of heart. Two days before Yom Kippur, Moscow was captured by Napoleon's army, but two months later, on the 15th of Kislev, it was driven back, and this was the beginning of Napoleon's rapid downfall." With the rout of Napoleon's army, the Alter Rebbe could proceed in a more relaxed and orderly manner on his journey. On Friday, the 8th of Teves, he and his entourage arrived in the city of Piena. This was one of the few non-Jewish cities or villages that welcomed them hospitably (even to the extent of offering free lodging and firewood).

As soon as he arrived in Piena, he began immediately to organize a relief campaign for all Jews who were affected by the war. He sent his oldest son (and successor, the Mittler Rebbe) HaRav Dov Ber to arrange housing for the refugees of the war. HaRav Chaim Avraham (his second son) was sent to nearby provinces to raise the necessary funds to help rebuild the many communities ravaged by Napoleon's army. Reb Pinchas Schick, a Chassid and extremely accomplished businessman, went to Vitebsk to coordinate the effort and find the most practical solutions of finding some means of livelihood for the refugees.

The Mittler Rebbe noted that, in one of the greatest acts of mesiras nefesh, the Alter Rebbe put his own life in mortal danger to do his part to defeat the evil ways of Napoleon. Indeed, the Alter Rebbe's ill-fated prophecy came to be, for the humbled last remnants of Napoleon’s army retreated out of Russia that Motzaei Shabbos at the time of the Alter Rebbe's histalkus [passing]. In a letter, the Mittler Rebbe writes, "Napoleon's total defeat will be when his own countrymen rise against him." That happened a year later.

Shortly before his histalkus, the Alter Rebbe said: "Anyone who will hold onto my klaymkeh [door handle], I will do him a favor [in return] in this world and the next one." The Rebbe the Tzemach Tzedek offered eight explanations for this statement. One of them is: "My door handle [or my ways] does not merely mean learning Chassidus. For the Alter Rebbe, through mesiras nefesh, instilled in Chassidim the practice of Ahavas Yisrael" - and Chassidim should live with it.

Rebbe Schneur Zalman’s fears were borne out by the events of the next two centuries. When emancipation did come to European Jewry, it came as a gradual process, and the traditional Judaism had by then developed an array of intellectual and moral responses (most notably, the Chassidic and Mussar movements). Still, the spiritual toll of freedom was high: traditional Jewish life was all but wiped out in France and Germany by the upheavals spearheaded by the French Revolution, and while it persevered in Eastern Europe until the eve of the Holocaust, many fell prey to the winds of anti-religious "enlightenment" blowing from the west. We can only imagine what the toll might have been had Napoleon conquered the continent in the early years of the nineteenth century.

Shortly before his passing (by one account, "after Havdala, several minutes before giving up his soul in purity to G-d") the Rebbe penned a short discourse titled, "The Humble Soul."

"For the truly humble soul," Rabbi Schneur Zalman wrote, "its mission in life lies in the pragmatic aspect of Torah, both in studying it for himself and explaining it to others, and in doing acts of material kindness in lending an empathizing mind and counsel from afar regarding household concerns, though the majority, if not all, of these concern things of falsehood.... For although the Divine attribute of Truth argued that man should not be created, since he is full of lies, the Divine attribute of Kindness argued that he should be created, for he is full of kindnesses... And the world is built upon kindness."

Zechuso Yagein Aleinu v'al Kol Yisrael - May his merits protect us all!

Monday, January 15, 2007

A7Radio: A Musical Exploration of the Song Dror Yikra

Different versions of Dunash Ben-Labrat's classic Shabbat song Dror Yikra performed by Oy Va Voi, Ben-Zion Shenker*, Aaron Razel, Gavriel Haviv, Aaron Bensoussan, Eli Chait, Natural Gathering, Beat'achon, Esta, Boaz Sharabi, Daklon, Moshe Tenenbaum, Jackie Makatin and more.

*yitz's note: the Modzitz recording of the Imrei Aish's composition, a waltz.

Wednesday, January 10, 2007

REBBETZIN SARAH FREIFELD, A HOME OF ROYALTY

Today, the 20th of Teves, is the yahrzeit of Rebbetzin Sarah Freifeld, the first wife of Rabbi Shlomo Freifeld, my Rosh Yeshiva. In tribute to her, here are some vignettes and sayings from around the web [slightly edited by me] and from the English Mishpacha magazine [Sukkos 5767 issue].

***

Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan, the well-known disciple of Sarah Schenirer, commented that out of the many excellent students she had taught over several decades, two students stood out: Rebbetzin Freifeld and Rebbetzin Leibowitz.

***

The Satmar Rebbe told one of his Chassidim, "In past times, women were davendik.".. Davendik means that on small baby steps you ask for help. On big ones, too. In formal prayer, too, but also when you're prayerful, full of inspiration, hopeful or defeated. To ask for that blessing, for strength and even for chen - to find favor, charm, grace in the eyes of others.

Another example of davendik is a mother of a large brood preparing school sandwiches and asking that each child's real needs be met that day, and day by day, slice by slice, sandwich by sandwich - and that the filling be sweet. A slice of life. So many situations must be addressed in private moments, heart-to-Hashem talks, outpourings, unburdenings. Rebbetzin Freifeld put it this way: "Hegyon libi lefonecha - Accept the thoughts of my heart, the unspoken but poignantly felt requests of my heart."

***

from a Microsoft “Converts to Judaism” group:

… the late Rebbetzin Chaya Sarah Freifeld, was a noted expert in Tehillim and founder of the first seminary for baalos teshuva* (Jewish women returning to Torah observance) in America in the late 1960s. This was one year before her husband, the late HaRav Shlomo Freifeld, founded the Yeshiva Sh'or Yoshuv in Far Rockaway for men. She not only knew all of the 150 Tehillim by heart, she had learned almost 100 commentaries on each pasuk (verse) of every one of the 150 Tehillim. At the end of the Shloshim (the one-month period of deep mourning after someone has passed away) for Rebbetzin Freifeld, a major Rosh Yeshiva pointed out that the Sages asked if a woman could have the status of Rebbe. He then went on to point out that Rebbetzin Freifeld was one of those special women who qualified -- because of her love of Torah, her phenomenal learning, her love of all Hashem's creatures and creations, and her ability to understand and counsel the many, many souls of all ages who came to her in her relatively short life. This is a family known for its depth of Torah learning, its tremendous chessed [kindness] to others, and for brining back countless Jewish souls back to their spiritual heritage.

*note: the Seminary was named Ayeles HaShachar, after a verse in Tehillim [22:1], and like Sh’or Yoshuv, not all the students were baalei teshuva.

***

from a comment to an article on Aish HaTorah’s website:

I practically grew up in the Freifeld house as a small child. What a special home it was and what a special man Rav Freifeld was. When he spoke to me it was as though I really was the most important person on earth. I remember spending Shavuos at the Freifeld house when I was about 9 years old. Rav Freifeld's daughter and I stayed up till midnight to "see the sky open," and we did. When we ran to tell him about it he took us completely seriously, as though there were nothing more important for a Rav to do in the middle of the night on Shavuos than sit and discuss the sky opening with two 9-year-olds. When I think about that home I think about love and warmth and acceptance for all Jews. I think that that was the first place that I was exposed to so many different kinds of Jews (and they definitely weren't the "mainstream" Young Israel type that I was used to in the 60s). The Rav and his Rebbetzin took them all in - loved them and nourished their souls and their bellies thereby turning many a hippie on to Yiddishkeit. When I think of an eishes chayil that I would like to emulate I think of Rebbetzin Freifeld zt"l. I feel extremely privileged to have been part of their home…

***

The remainder is from the English Mishpacha magazine - Sukkos 5767 issue.

A HOME OF ROYALTY

The home that he [Rabbi Freifeld] and his Rebbetzin created was as much a part of the Yeshiva as the Beis Medrash and the dormitory, and for years, the yeshiva had no dining room**…The exposure of young couples to the unique relationship between the Rosh Yeshiva and his Rebbetzin…was a glimpse at the potential of the Jewish marriage to transcend pettiness and ego. “It was a magnificent partnership, his marriage embodied royalty.”

**a personal note: Many of the talmidim at the Yeshiva, and talmidos at the Seminary, partook of their first Shabbos meals at Rabbi and Rebbetzin Freifeld’s Shabbos table. Many of us remember with great fondness the Rebbetzin’s gefilte fish: it was a huge oval ball, just the right texture, and spiced with an extra dose of pepper. The Rebbetzin once told my wife that her fish wasn’t always so good. In fact, she had to discard many “failed” batches of fish before she perfected her recipe.

***

A talmid once asked him how he could be a flexible husband without becoming a “doormat”. Rebbe answered him, “People say it’s shver tzu zein a Yid, it is difficult to be a Jew. They are right, and the reason is because a Yid has a responsibility to be misbonen, to contemplate his course of action, to consider what is expected from him in each situation. There is no right answer, because you have to weigh each situation anew.”

Rebbe then shared a personal example. “Recently, I was going to the doctor, and my Rebbetzin asked if I preferred to wear shoes or slippers. Though slippers were more comfortable, I wanted to wear shoes, so as not to feel like a choleh [sick person]. I wanted to wear shoes to show kavod [honor, respect] for myself, for the doctor, and for the people in the waiting room.

“Then I stopped to be misbonen. If I wore shoes, who would be the one to lace them? I certainly couldn’t. My Rebbetzin would have to bend down and do that for me. What about her kavod? I wore slippers.”

***

After the Rebbetzin passed away [it was around 1983], one of Rabbi Freifeld’s close talmidim accompanied the aron [coffin] to the burial in Eretz Yisrael, and when he returned to America, he made his way directly to Rebbe’s home. The room was filled with distinguished Roshei Yeshivos who had come to be menachem avel [pay their condolences], and Rav Shlomo introduced this talmid by saying, “Achim b’tzara, brothers in anguish.” He had drawn his beloved talmid into his own suffering, allowing him to share his Rebbe’s distress.

Tehi zichra baruch – may Rebbetzin Freifeld’s memory be for a blessing!

Monday, January 08, 2007

The BNEI YISSASCHAR Sure Can See!

THE YAHRZEIT OF THE "BNEI YISSASCHAR" and

The BNEI YISSACHAR's Music.

Be sure to check them out!

This year, I’d like to present a very special story from our good friend Yrachmiel of Ascent Institute of Tzfat. Enjoy!

THE GENEROUS TEACHER

from ASCENT of SAFED

After we finish our festive meal at the Seder, it is customary to "open the door for Eliyahu HaNavi - Elijah the Prophet". It is said that if we see anyone when we open the door, it is Eliyahu.

When the Bnei Yissaschar was ten years old, his father took a position as a teacher in a distant town. The Bnei Yissaschar's father spent the duration of the winter in a Jewish-owned inn. In those days it was normal for a schoolteacher not to see his family from October to April.

That winter was particularly bitter. Snowstorms lasted for a week. During one such storm, a knock was heard at the door. The innkeeper opened the door and found three half frozen Polish peasants requesting a place to stay. He inquired of their ability to pay and found that their combined funds were not enough for even one night's stay. The innkeeper closed the door on them. The schoolteacher was shocked. When he complained to the owner, the owner merely shrugged and responded, "Do you want to undertake their expenses?" Much to the innkeeper’s surprise, the teacher agreed.

The peasants thanked their benefactor and proceeded to enjoy themselves at his expense. That storm was particularly brutal and the peasants remained in the inn for two weeks. After the snow cleared enough for passage, they thanked the schoolteacher profusely and left.

Pesach [Passover] approached and the Bnei Yissaschar's father went to settle his account. The innkeeper figured he owned the teacher 40 rubles for teaching his children, but the teacher owned him 43 rubles for taking in the peasants. The innkeeper wished him a happy Pesach and said he could bring the three rubles upon his return after Pesach.

The father did not know what to say. He bid his host farewell and left. He traveled to his village, but could not bring himself to go home. He stopped into one of the local synagogues, opened a tome of the Talmud and immersed himself in study. In the meantime, his son heard that his father was in town and went looking for him. He found his father in the shul.

The Bnei Yissaschar ran to his father and with great emotion begged his father to come home. He wanted to show his father his new Pesach shoes and clothes and all the other things mommy had bought (on credit). This made the father only feel worse. As they walked home, a chariot came rumbling through the streets. The streets of that hamlet were very narrow and pedestrians were forced into alleyways to avoid be trampled. As the coach passed by the two, it hit a bump and a parcel fell off the back. The Bnei Yissaschar's father picked it up and began running after the coach, but was unable to get the coachman’s attention. The coach turned a corner and disappeared. The Bnei Yissaschar's father, seeing no distinguishing marks on the bag, understood that in such a situation it may be presumed that the owner would relinquish all hope of its recovery, and since there was no possible way for him to locate the owner, therefore it was his to keep. He opened it and found exactly 43 rubles.

Opening the door for Eliyahu HaNavi on Seder night

The night of the Seder, the Bnei Yissaschar was given the merit to open the door for Eliyahu. When he opened the door, he called to his father, "Ta, (Yiddish for ‘Dad’) the coachman is here!" There was no one there. The Bnei Yissaschar's father pulled the boy aside and told him that he must promise never to tell anyone this story until he was on his deathbed.

This story was told to me by a rabbi who heard it from a student of the Bnei Yissaschar, who heard directly from the Bnei Yissaschar on his deathbed!

Lightly edited from the weekly e-letter of Rabbi Herschel Finman of Detroit - Shliach613@aol.com